The Paper Chain

Late 19th and Early 20th Century Stationery at Woolworth's

Three stationery lines were among the first fifty things Frank Woolworth stocked in Utica in February 1879. The tiny, makeshift 'Great 5¢ Store' sold simple 'writing books', Pencil Charms and turkey red paper napkins.

He recognised their potential. They could be mass-produced at a very low cost. The early writing books were made up of folded pages with a semi-stiff cover, held together by two staples. By persuading a paper mill to set up a simple assembly line, it was possible to knock out a thousand every hour. This allowed him to offer what had been a 25¢ value for 5¢ as his Syndicate expanded.

As branches began to attract office workers simple accessories like drawing pins, paper clips, treasury tags, and ring reinforcers were added. Initially they were sold in simple gummed envelopes, but as sales grew he was able to obtain stock in small boxes carrying his distinctive 'Diamond W' motif.

He had imagined that most shoppers would only want practical items. But he found that, like his own family, poorer folk put something by for special occasions, and liked to splash out on the occasional indulgence. As he began to target cities as well as more rural locations, businessmen appreciated his value and made a ready market for items like paper and ribbons for typewriters, carbon paper, and ruled account books.

Frank's brother Charles Sumner Woolworth had join him in the dimestore trade just weeks after the first opening. The youngster had added 10¢ lines to boost trade. Frank had quickly followed suit. Within ten years the pair had built a formula strong enough to finance the fit-out costs and higher rents for city centre branches, and had switched from back street locations to prime spots.

These premises had an even wider appeal. As well as housewives and farmers they attracted office and factory workers, and even captains of industry. Some preferred the rock-bottom prices of the simple 5¢ lines, but others were drawn to elegant packets of fancy envelopes tied in a ribbon for a dime. They were happy to pay the extra for watermarked writing paper in a gentle lilac colour with a slight scent, knowing that it would cost a dollar or more in a Department Store.

In 1890 Frank Woolworth discovered a new way to satisfy the demand for luxuries at affordable prices. As Buyer-in-Chief, he selected the lines personally. This brought him into contact with many wholesalers, who added commission to the cost price. This prompted him to trace his best-sellers back to the source. The detective work led him across the Atlantic to Europe, where factories had embraced new technology to automate the production process. Before long his twice-yearly trips to Europe became the source of many of his best lines in North America.

For example in the London Docklands he found a factory that made luxury writing pads and envelopes. They had invested in sophisticated machinery to automate the production process. Their goods were made and packed by giant machines. Workers loaded them with raw materials and took the finished items away, rather than packing them by hand as they did in the USA. The much higher throughput made the cost much lower, making it affordable to pay the cost to ship the goods to New York and drop the price from 10¢ to 5¢ while still achieving a margin of almost 3¢ a pack.

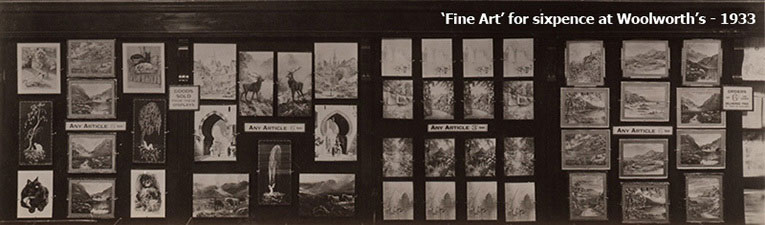

Five miles to the south, among the villas of Brixton, he found a printing works that had developed a technique to hand-tint black and white photographs to produce postcards in full colour. They were happy to take high quality snaps of local views from the USA and absorb the cost of the labour-intensive tinting in exchange for a large order. Soon the cards were racing off the Syndicate's shelves, proving to be winners at 5¢ a piece.

Over time European imports became increasingly important to the 5 & 10¢. In 1900 they accounted for a full quarter of the goods sold and, more importantly, their high margins were behind half of the chain's annual profit.

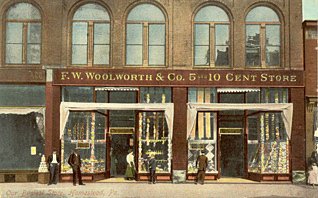

Many monochrome pictures views from the USA got the 'pseudo-color' treatment. Charles Sumner Woolworth enjoyed particular success with them. Store Managers liked to stock pictures of their own branches as well as the local area. Fortunately the five-and-ten's public profile ensured a swift sell-through. Surviving examples are often inscribed on the back with a comment about the store or an item that it had sold.

The regular transatlantic trips set Woolworth musing about the feasibility of opening a British Five-and-Ten (or 'penny and sixpence') subsidiary.

The pipedream became a reality in Liverpool on 5 November 1909, soon followed by five further outlets spread in a line from the West to the East Coast of Northern England. Success in Liverpool, Preston, Manchester, Leeds and Hull proved the concept and opened the door for the first opening in the capital. Brixton was chosen as a swanky, leafy suburb on the outer edge of London, standing three miles south-west of the smokey city.

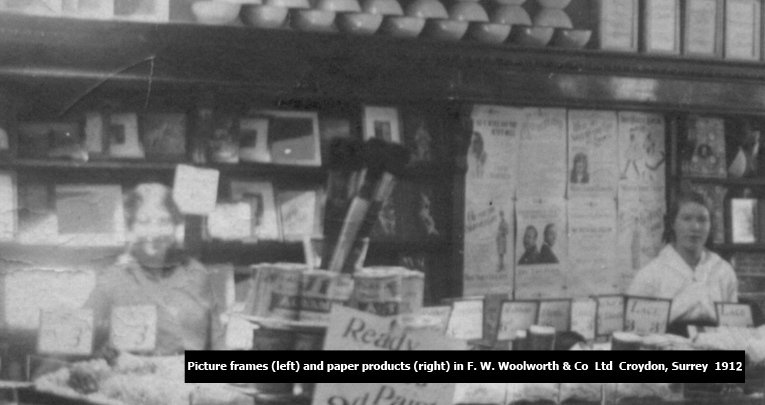

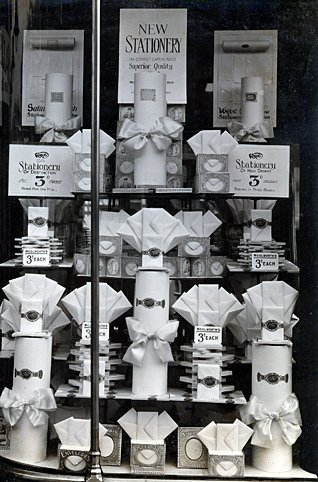

The British Buyers pitched the Stationery near to the store front. Many of the items were able to draw on the same local factories which supplied the stores in the USA. There was one important difference. Without the cost of Transatlantic Shipping the pads and pens were sold for a penny and threepence, instead of the stateside prices of 5¢ and 10¢. Threepence and sixpence at the time were the equivalent of 6.08¢ and 12.17¢, while a penny was just 2¢ At today's prices a penny item would be 35p, a threepenny item £1.05 and a sixpenny one £2.11. This allowed Woolworth to go head-to-head with the Penny Bazaars of Marks and Spencer, and to offer prices that others found hard to match.

The surprise best sellers in the first British range were picture frames and albums. Many High Streets and seafronts included photographers' studios or booths which offered family portraits or silhouettes at a penny a piece. Woolworth was able to capitalize on this with a way of showing off the images or preserving them posterity. A pair of simple frames in the Liverpool range had quickly blossomed into a large collection of shapes and sizes, some with glass panels and some without, by the time the Brixton store opened. These had been chosen to match the size of the little portraits, with others suiting the enlargements pushed by the booths at prices of up to a shilling. Simple loose-leaf folders and packs of cardboard inserts provided an adaptable way of making an album, later complemented by fully bound designs. Other best-sellers included gummed luggage labels, pencil sharpeners and india rubbers, as well as a British equivalent of the Diamond W Exercise Books.

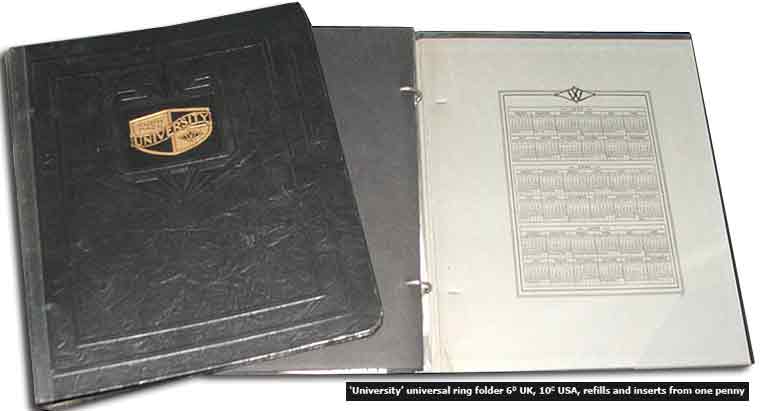

The Buyers were able to draw on expertise built up during thirty years trading in the USA. The loose leaf folders were an example of an item that had more than one purpuse, which boosted the volumes that could be ordered and guaranteed the lowest possible price from the supplier. As well as photo albums, different inserts transformed them into notebooks by adding ruled paper, calendar sheets to make a diary, or stamp or coin albums with purpose-made mounts. Seventy-five years later the same concept lay behind the filofax, which became a must-have designer accessory in the 1980s.

Far from being throw-away items, some of these early products were cherished by customers for many years. For example, rather than disposing of a diary at the year-end, the stores offered "penny stick-overs" to insert a new calendar on the inside front cover of the binder, and new day- or week-to-a-view pages to complement or replace the existing inserts. The stores' watchwords of thrift and economy met with approval from the clientele, but also generated margins of up to eighty percent.

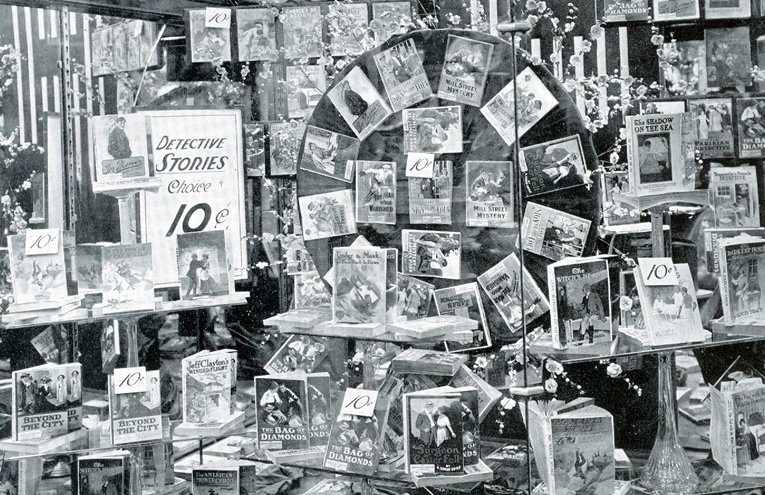

Budget books became a great favourite on both sides of the Atlantic. They first appeared on the shelves in 1896. Initially Frank Woolworth bought bin ends of job novels as an experiment. They proved to be a hit in rural areas, where romances and tales of daring-do provided an exotic escape on a long winter's evening, and a smash in the Cities where they found favour with office workers and commuters. Later, when Charles and Albert Bonni shared their plans to build a Little Leather Library of small classic books with leather bindings, Frank Woolworth was quick to snap them up. In 1917 more than a million volumes were sold at the 5¢ & 10¢

Novels featured in the first British stores, and soon won a strong following. They were treated as an exception to a general rule that Woolies would not mention its American roots. Men loved detective fiction and stories of Cowboys and Indians, as well as anything to do with the movies. The counters were plastered with signs boasting "the latest titles from the US of A" A separate section was squarely targeted at their wives and lovers, selling sixpenny romances by the thousand.

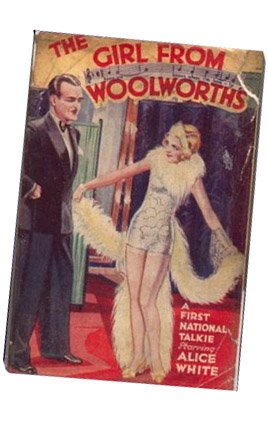

One title was a gift to the stores, selling in record numbers. Karen Brown's 'The Girl from Woolworths' told the story of a shop assistant whisked from the counters of the 5¢ & 10¢ to a career in the movies, before giving it all up when she found true love. Publication was synchronised with the release of a movie version, which was one of the first talking pictures. Aware of record-breaking sales in North America, Company bosses placed huge advance orders and planned spectacular window displays to mark the British and Irish release of the film, even commissioning a commercial to play in the cinema alongside the film. Their efforts were rewarded with record-breaking sales.

From the earliest days Woolworth had adapted its range each season. To keep the offer fresh, items were introduced to align with each major calendar event. There were special window displays of gifts for St Valentine's Day, Easter, Thanksgiving and Christmas, along with special features of essentials for Spring Cleaning, the holidays and Back to School. The Woolworth promotional calendar was already firmly established when the brand crossed the Atlantic, helping the threepenny and sixpenny stores to quickly establish market leadership for the key seasons. One season in the calendar was always treated as being twice the length in Britain as the same event in the USA. The decision to put the Christmas range on sale at the beginning of October allowed the stores to skip the Thankgiving celebrations while generally following the same pattern. It spawned a number of adages like "you can tell it's Christmas at Woolworth, because the Easter Eggs are out"!

The Founder had found his displays of 'school sundries' particularly successful each summer. It provided an opportunity to showcase his range of stationery in the windows, and to sustain the brand by attracting the young generation inside. The idea was adopted from day one in the UK and was later bolstered by a window dressing competition on both sides of the Atlantic. The winning displays were photographed, with copies circulated to every store around the world. 1930's overall winner, submitted by the branch in Little Bluffs, Arkansas, was subsequently copied in locations as diverse as Quebec, Havana, Berlin, Edinburgh, Cardiff and Dublin.

The traffic in ideas stretched both ways across the Atlantic, with displays from Liverpool and Birmingham repeated stateside, and products chosen by the British Buyers often inspiring similar lines to be purchased by their counterparts in New York City, Montreal and, from 1927, Berlin.

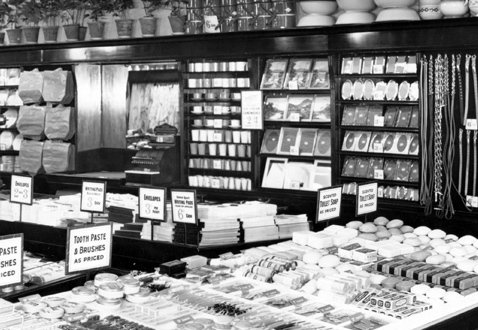

In 1934 the six hundredth British outlet opened in Wallington, Surrey. The chain had become firmly established, with few customers knowing of its American roots. One of the keys to success had been consistency of display and operation between one store and another. This meant that whichever branch a customer visited, whether in a rural corner of England or a big City like Glasgow or Belfast, they would always find the stationery department on the right hand side of the store, straight inside the main entrance and next to the displays of toiletries and cosmetics.

The 'nothing over sixpence' formula and national presence gave unrivalled buying power. The stores sold huge quantities at very low prices. They attracted big crowds on weekdays and were always packed at the weekend.

The average sale of each stationery item exceeded one gross (144) per store per week. Most had high margins too. No wonder the counter was at the front !

By the 1930s Woolworth was highly profitable. It kept back some of the cash it generated to open more stores, and to upgrade the existing branches with more space and better counters. Fearsome Superintendents checked that the signs were sparkling clean, the counters were dust-free and the service was 'attentive'.

Before World War II most items were sold unwrapped or with minimal packaging. Most shoppers used their own bags rather than requesting one in-store. Signs and labels were refreshed every few months to keep the offer fresh but, with this exception, similar successors to many of the items shown on the Liverpool displays could still be found in the range seventy-five years after the picture was taken. Good buying and clever marketing had helped the stores to maintain strong staionery sales throughout all of that time.

Shortcuts to related content

Stationery, Cards and Books Gallery

Early US and UK stationery items

The cards our grandparents sent

P-p-p-pick up a Penguin (originally at Woolies)

Picture Histories - all time best seller

Museum Navigation