Just sew

A thrifty guide to a century of

patterns and thread from F.W. Woolworth

On its opening day, 5 November 1909, the first British store in Liverpool offered a range of fashions, along with a counter full of 'penny notions', the name its American owners had given to the range that is more commonly known as Haberdashery, or Hab'y for short.

Part of the chain's brand essence was a self-imposed maximum price of sixpence (2½p). As a result, rather than selling made-up clothes, it specialised in selling everything that people would need to make their own garments at home.

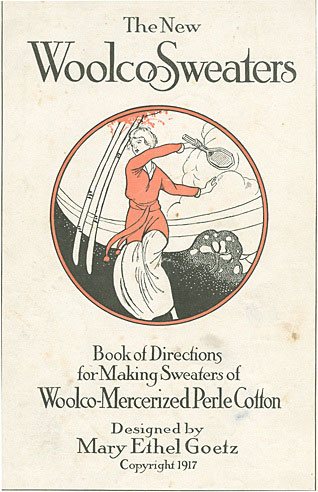

Life was very different in Edwardian times. Most homes had gas lighting and were heated by coal fires. There was no television or radio. A popular pastime on long winter evenings was to knit or sew. Many women repaired the family's clothes, and some also made garments from scratch, guided by a paper pattern.

Whatever the project, whether making a sweater or mending a rug, Woolworth had the right needle and materials. It had wool and yarn, cotton and thread, and even the scissors, often for a penny, with everything costing no more than sixpence. Adjusted for inflation these prices would range from 17p to £2.11 or 20¢ to $2.59 today. Such value made the stores first choice for thrifty mums on a tight budget.

Many patterns were ideal for beginners. At the time most girls were taught needlework at school, in preparation for a life minding the home. Today life has changed beyond recognition, yet many of the garments still look quite fashionable, in a retro kind of way!

Thrifty shoppers could get everything needed to make a whole outfit for less than ten shillings (50p), which at the time was much less than it would cost to buy the finished garments. Yet falling prices over the last century mean that today, if you shopped around, you could get a decent off-the-peg look for the equivalent price of £42 ($50).

When Woolworth first opened in Britain, it was one of the only international chains. It drew on thirty years of experience in the Main Streets of the USA, and incorporated design ideas from its stores in Canada and Buying Offices in France and Germany. The goal of the Buyers was to imitate the latest catwalk fashions from Paris, Milan and New York at sixpenny prices.

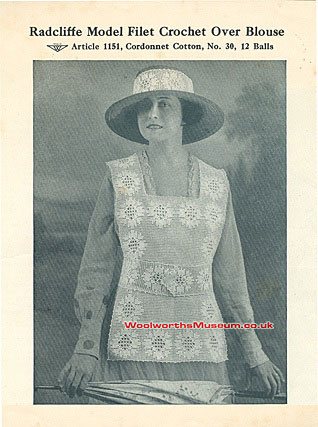

The crocheted blouse illustrated could be made for half a crown (2s6d or 12½p) n the 1910s, equivalent to around £10.50 or $12 today.

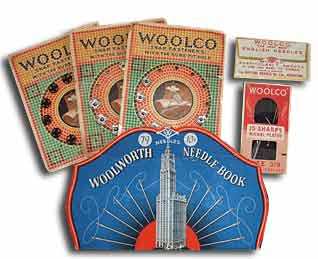

In a twist of fate, most of the patterns sold in the UK were printed in the USA, but the reverse was true of the accessories and threads sold in America, which were British made. Sheffield steel and Redditch needles had become famous across the world. The factories that made them were highly automated, achieving the highest quality at the lowest price.

As work neared completion on the Woolworth Building in New York, which was the world's tallest, Frank Woolworth travelled to the Midlands to invite the British Needle Co. Ltd. of Redditch to make some of his souvenirs. He was impressed by their artwork for the sleeves, and went on to sell needle books by the million.

Two years later, German U-Boats interrupted the supply-line across the Atlantic. The 5 & 10¢ supremo had to act decisively to maintain supplies of the best-selling line. He showed an American factory how to make the needles, based on his observations on his visit to Redditch. Such work in stimulating American industry established his reputation as a merchant prince and a pioneer of mass-production in the USA.

As the chain expanded across the UK and Ireland and its stores grew larger, the haberdashery department was expanded with new ranges. By the 1930s there were pre-fabricated components like sew-in pockets and decorative fabric panels. The accessories included sparkling sequins and sew-on jewellery adornments for dresses, as well as a wide array of fancy buttons and zips. Customers were also encouraged to tackle more ambitious projects, making their own toys, lampshades and even rugs.

In the 1930s the company had its headquarters in New Bond Street, Mayfair, just yards from the heart of the London fashion scene in Regent Street and Savile Row. The Buyer soon got to know many fashion executives socially, and was able to use the relationships to add spice to his range. When a fashion house had made too much of a line, or had an order cancelled, he snapped up the stock and rushed it out to the shelves.Treasures like silk stockings and fancy knickers caused mayhem in the stores when put on sale for sixpence. Customers besieged the fashion counter to grab a bargain as soon as the word spread around town.

It became a standing joke that when well-to-do shoppers bumped into their friends, both would claim they were buying for a friend, or for a child's school play. Whatever the truth, Woolworth's had established itself as the everyday store for everyone.

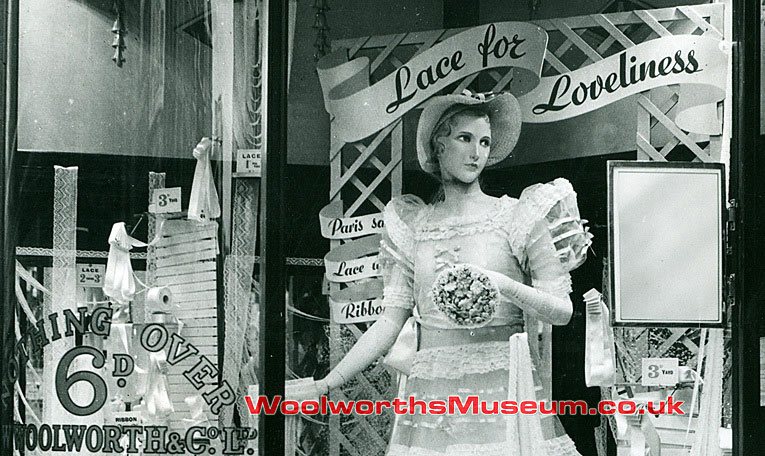

The picture below shows the store in Chiswick High Road, West London in 1936. The window is captioned "Lace for Loveliness" and features some of the things people could make with a large consignment of lace that the Buyer had bagged in one of his schemes.

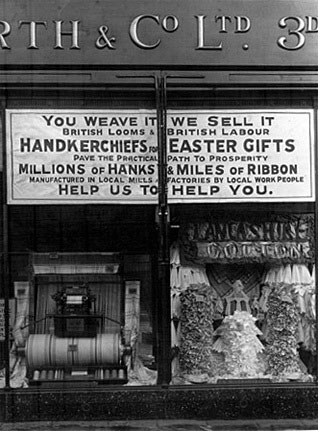

The 'everyday store for everyone' image was reinforced by local initiatives, targeted to specific areas with help from the suppliers nearby.

For example, with over a hundred outlets in Lancashire, the District Manager persuaded the largest mill in the county, Horrockses of Preston, to loan one of its smaller looms. To accompany it he commissioned a signwriter to make a large banner saying:

'You weave it, we sell it.

British looms and British Labour.

Handkerchiefs for Easter Gifts.

Pave the practical path to prosperity.

Millions of hanks and miles of ribbon.

Manufactured in local mills and factories by local work people.

Help us to help you.'

A carefully-crafted timetable transported the loom, signs and contents of the window display from one store to the next across the county, targeting local wakes week holidays. As well as boosting sales, the gesture created priceless goodwill, and is still fondly remembered by some Lancastrians to this day.

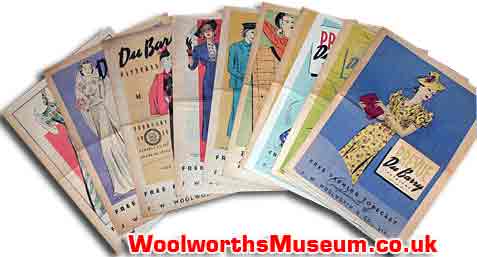

Du Barry dressmaking patterns became very popular in the 1930s. Each one included drawings and sewing instructions; some also had a cut-out of the outfit. There were patterns for all sorts of things, including dresses, blouses, hats and even men's suits.

Innovative marketing was used to drive sales. A teaser version called Free Fashion Forecast was given away to customers. This showcased the latest designs, with enough detail to help readers choose. The measurements were omitted to make them buy.

Example of a DuBarry Pattern converted into a downloadable Adobe PDF.

(Download a free copy of Adobe Reader)

The stores stocked paper patterns until the mid 1980s. Until 1965 the price was generally held to sixpence. Multi-pattern booklets were even better value at a shilling (5p) each.

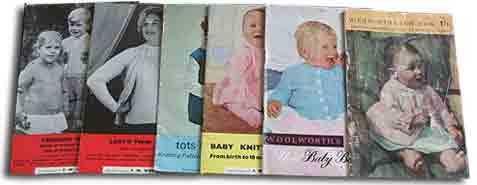

Like the Fashion Forecasts of the past, the booklets were treated as a sales aid for the extensive selection of wool, cotton, needles, zips and buttons that were available in-store.

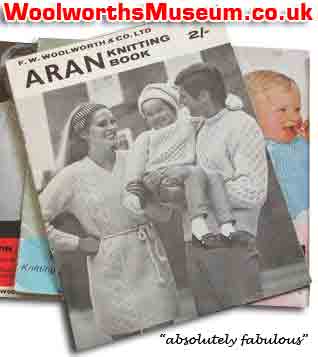

Each pattern was carefully crafted. The goal was to persuade shoppers that the garments were easy to make. They promised that a skilled knitter could create a stylish and fashionable look to be proud of. To achieve this, the Buyer commissioned a full fashion shoot for each batch of patterns, paying top-dollar to secure the best models that money could buy.

Talent scouts chose models from drama schools and beauty parades, picking artists who they believed were 'going places'. The patterns show that they knew their stuff. Among those pictured in 'Woolies' Woolies' were the Gurkhas' champion and absolutely fabulous Joanna Lumley, and the shaken but not stirred Persuader and super-sauve James Bond, Roger Moore.

In between the patterns, each booklet was crammed with advertisements for the extensive range of accessories stocked in every Woolworth's haberdashery department. By the 1960s the range in the largest superstores had expanded to include material by the yard, and even electric sewing and knitting machines.

You can see more window displays and paper patterns in our tribute to Woolies fashion - The Easter Parade, here in the Fashion and Ladybird gallery of the Woolworths Museum. Why not take a look?