Withdrawal from the Republic of Ireland

The plunder of Woolworth, 1984

Over seventy years of trading Woolworth's had established itself at the heart of Irish shopping. It had nineteen branches spanning most of the major shopping locations in the Republic, which sourced about 80% of their range locally, offering Irish equivalents to the items carried on the British mainland and in Ulster.

The retailer had deftly integrated its stores into local life, gaining acceptance as quintessentially Irish. Thus it had stepped around understandable resistance to all things British in turbulent times. It had built a strong team locally, with many store staff devoting long careers of over forty years' service. Over time a number of the Managers who had been parachuted in from across the water chose to stay. It seems the quality of life prompted them to abandon the rat-race of relocations to climb the greasy pole.

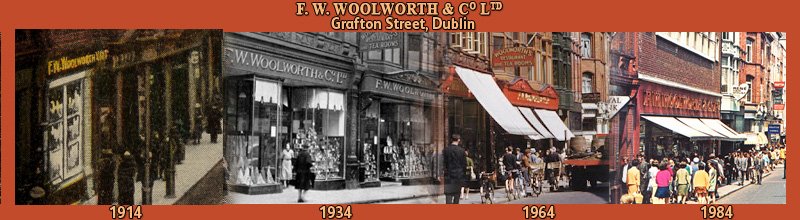

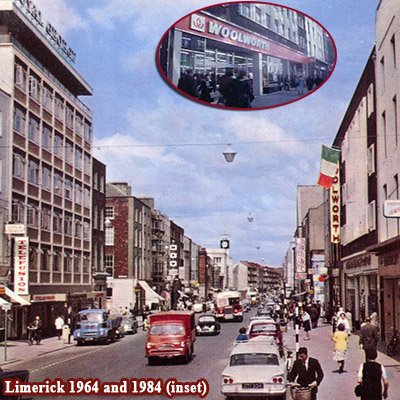

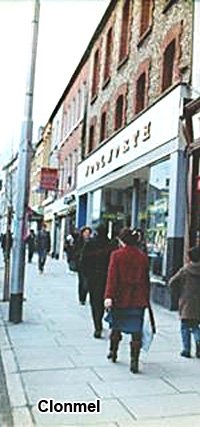

Time had not stood still. The buildings had been well maintained and more had been modernised than in the UK. For example Grafton Street had been rebuilt in the modern style in 1966. Its new look mimicked an identical transformation which had recently been completed at the outlet in O'Connell Street, Limerick (left). Both had proved popular locally. In the Seventies Cork and Tipperary had also had makeovers. In 1980 alone the units in Henry Street Dublin, Limerick and Waterford had all been modernised, while Galway had been the last store to be refurbished before the American majority shareholders had sold out in 1982.

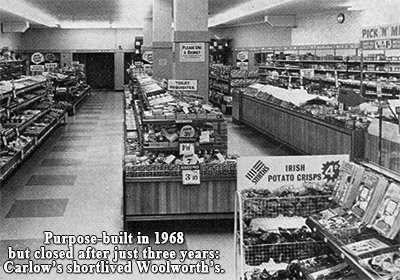

At the same time under-performing stores had been weeded out. The branch in Thomas Street, Dublin, which had been a disaster, had been closed in the Sixties, followed by Carlow, which had pioneered self-service in the Irish chain (1971), and the branches in Bray (1973/4) and Thurles (1978). The management had even bitten the bullet, admitting that the modernisation of Tipperary had caused its sales and profit to collapse, closing the doors for the last time in 1978. All of these branches had one feature in common: they had been opened in the boom days of the 1950s, a time when the Company had routinely ignored its own projections and opened in any town where space became available. Having taken the pain, everyone in the Irish Company believed it was well-placed to face the challenges that lay ahead.

Snapshot of F.W. Woolworth & Co. Ltd. in Ireland, January 1984

Store

Dublin, Grafton St

Dublin, Henry St

Cork

Dun Laoghaire

Limerick

Dundalk

Tipperary

Kilkenny

Sligo

Waterford

Clonmel

Drogheda

Wexford

Tralee

Bray

Galway

Mullingar

Thurles

Ballina

Dublin Thomas St

Killarney

Cavan

Carlow

Opened

1914

1918

1920

1920

1921

1928

1954

1930

1930

1930

1931

1950

1952

1952

1953

1953

1953

1953

1953

1954

1954

1955

1967

Tenure

Lease (2007)

Lease (2000/23)

Lease (2010)

Lease (2002)

Lease (2011)

Rented

Freehold to 1978

Rented

Rented

Lease (2015)

Rented

Freehold

Rented

Freehold

Lease to 1973/4

Freehold

Freehold

Freehold to 1978

Freehold

Freehold to 1960s

Freehold

Freehold

Freehold to 1971

Refurbished

Extended 1966

Full 1980

Full 1974

Budget 1972

Full 1980

Full 1968

(Closed)

Budget 1973

Budget 1974

Full 1980

Budget 1972

Full 1966

Budget 1973

Budget1971

(Closed)

Full 1982

Budget 1974

(Closed)

Budget 1974

(Closed)

Budget 1973

Budget 1973

(Closed)

Sales £M 1983-4*

1.6

4.3

1.5

0.4

1.2

0.6

N/A

0.5

0.5

0.7

0.5

0.7

0.9

0.9

N/A

1.7

0.3

N/A

0.3

N/A

0.4

0.3

N/A

Salaries %

16.3%

17.1%

16.1%

14.5%

12.5%

13.3%

N/A

11.7%

13.8%

12.7%

12.8%

12.7%

11.8%

11.2%

N/A

11.1%

13.0%

N/A

13.6%

N/A

9.7%

10.8%

N/A

NOTES: 1. The term 'rented' is used to denote stores where leases had expired between 1970 and 1982 and had been renewed at market rates with five-yearly breaks for both parties.

2. *Sales are shown in sterling, inclusive of Irish VAT at a rate of either 35% or 23% by product group

3.Salaries % shows the expenditure on staff and management wages calculated as a percentage of the turnover shown in the sales column. It should be noted that the average cost to sell of 13.8% is much higher than the British rate of 12.5%, even without adjusting for the distorting effect of the higher rate of VAT in Ireland.

4. 'Budget' refurbishments, known internally as 'crash conversion', reconfigured and repainted the counters. Every expense was spared. Shelving was replaced only at the store front as new cash and wrap desks were added to facilitate self-service operation.

5. Sources: F.W. Woolworth & Co Ltd Annual Reports (1960-1982),Woolworth Holdings Ltd Annual Reports (1983-1985), unpublished propety audit by Hillier Parker Ltd, commissioned by the Company, unpublished statistics from the FWW Management Information System. 'Phoenix - Strictly Private and Confidential' ring bound and serial numbered report by Charterhouse Jaffet (1982)

Crackdown meltdown

1980 had brought a severe recession, hitting both Britain and Ireland. The Woolworth Chairman, Geoffrey Rodgers, had responded with deep price cuts across five hundred top selling lines, marketed as 'Operation Crackdown'. This had attracted shoppers and boosted sales, but at a cost. The profit per item, known internally as 'Merchandise Book Gross', had fallen steeply. The sales increase had been insufficient to cover the shortfall. In parallel new employment regulations and steep price inflation had caused the wage bill to rocket. This had particular ramifications in Ireland, where staff had enjoyed a significant premium over the UK rate for many years.

Crackdown's 'pile it high, sell it cheap' philosophy caused disquiet in the City. It flew in the face of all the work that Rodgers and his predecessors had done to take the brand up-market. The brokers' worries soon made headlines in the press, with some dubbing the strategy "the blunder of Woolworth's".

It was against this backdrop that a group of financiers, backed by Merchant Bankers from Charterhouse Jaffet had seen an opportunity to pounce. The consortium had worked in secret to profile the company and had compiled a detailed plan of how to turn a profit on the deal. It code-named British Woolworth 'Phoenix' and had dug up every scrap of published knowledge about its finances and operations. A summary of the battle plan dubbed Phoenix's Board 'lost' and its business 'out of control'. But it had got two things right; it had modernised almost half of its stores in the Seventies, and it had acquired B&Q. The in-depth analysis had revealed hidden value unknown to the Boards in London and New York, stemming from a mis-valuation of the real-estate. This had proved the deciding factor in making a pre-emptive bid to take control by buying out New York's golden share. The timing had been perfect. Across the Atlantic cash was tight. Millions of Bonds that had been issued in the 1960s were due to mature at a time when the coffers were unusually empty. Thus a deal was struck above the heads of the British Board, and subsequently approved by the great majority of British shareholders, to sell the US stake to the consortium, which had named itself Paternoster Stores Ltd, after the street in the City of London where the bid had been hatched.

Sugar and spice but not all things nice

The new owners had recently wowed the City, earning their spurs at British Sugar. They had modernised the nationalised business, which had been in public ownership since 1936. The Silver Spoon brand had been developed to raise the Company's profile. This had helped to attract new investors to a rights issue in 1977, reducing the Government's stake. Loss-making plants had been closed and efficiencies had been pushed through. This laid the foundations for an outright sale to S. & W. Berisford Ltd., British Sugar's largest customer. The sell-off was a lesser-known one of many privatisations during the Thatcher years. The sale completed in 1982, freeing the former Directors to seek a new challenge. It was this that had drawn them to Woolworth. While their principal skills were financial, the Deputy Chairman, Peter Firmston-Williams, had been a Director of Asda and remained a Director of British American Tobacco, which had acquired Argos in 1979. He would oversee a recruitment process to hire a hard-hitting CEO for the Woolworth Stores.

Documents passed to the Woolworths Museum reveal that the business case centred on selling Woolworth freehold properties to repay bridging loans from Charterhouse Jaffet. Whole layers of management would be stripped out and cash would be released by clearing old stock and then managing inventory better. The battle plan noted that B&Q had potential, while reserving judgement about its acquisition of Dodge City. It did not consider that any of the other new ventures of the Sixties and Seventies had merit, marking them for early disposal. It also modelled the effect of reducing the Woolworth store-base by some 40% to just 650 small and medium stores, concluding that, by doing so, it would be possible to pay Paternoster a one-off dividend of £223 million after tax in 1986. It notes: "Charterhouse Japhet has received an opinion from Richard Ellis supporting as reasonable the expectation that realisations can be made to this extent and in the proposed time scale so as to produce the values projected."

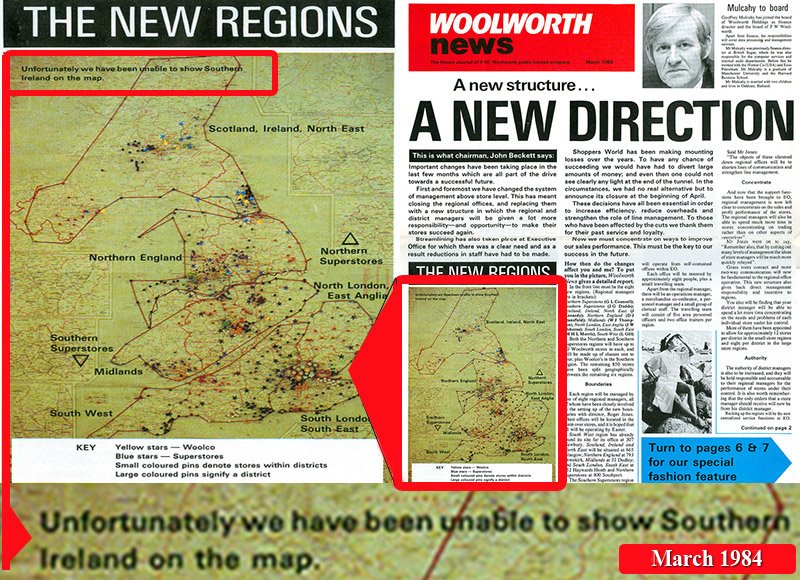

The same document highlights the fact that the overseas interests accounted for only 3% of turnover, classifying the stores in the Irish Republic in this category alongside the far-flung branches in the Caribbean, Africa and Cyprus. As well as appearing in the business review section, the point is repeated to introduce a recommendation to 'simplify' the operation with the added benefit of releasing funds to pay down debt, all without making a signficant impact on turnover. In other words, the writing was on the wall for the Irish Stores before Paternoster had even seen the books or taken control of the business.

After the takeover, public pronouncements made no mention of such radical plans, despite being perceived as tough. The new Board told the Union of Shop, Distributive and Allied Workers, which had been officially recognised despite representing only 8% of the UK staff, that unprofitable branches would be closed. The Directors' initial assessment had identified thirty-seven locations which fell into this category and would have to go, as well as Shoppers World, which had been summarily closed, with most of its assets snapped up cheaply by British American Tobacco to augment Argos. The new management laid down the gauntlet to the rest of the Woolworth stores, explaining that 'Operation Facelift' (a turnaround plan) was underway. This would give every branch the tools to achieve a semi-net profit (profit before central overheads are deducted) of at least 10%. The Board would examine any store that failed to meet this hurdle by the end of 1985/6, with a view to possible closure. USDAW agreed this was fair.

Seeing red

The Irish stores embraced 'Facelift', keen to impress their new bosses and recognising the need to smarten up. Many an evening through 1983 was spent relaying the salesfloors, stripping stock to the floor, scrubbing shelves with Ajax and Scotchbrite pads (from Dept. 341), dismantling and removing some counters, squirting the floor with Winfield Washing-up Liquid and dragging whole gondolas into new positions. The goal of the wider gangways was to make the stores appear more spacious. To keep costs low, Managers stayed late unpaid to supervise teams of local decorators repainting the walls and windows above the cornice line. The 'muppets at Marylebone' had specified a deep geranium red for the walls and 'Poppy' gloss for the frames. "For maximum impact ceilings should be restored from yellowy grey to white if necessary", they decreed.

The Managers at Henry Street Dublin, Waterford and Limerick must have had to bite their tongues as Coverplus Macpherson's paint was slopped all over the elegant striped, pastel-shaded laminate above the counters, which had been a highlight of their refurbishments just three years earlier. The designer feature had been commissioned to give the stores a cleaner and more modern look, and had been well received. The Executives behind 'Facelift' had pre-empted any complaints about the 'red revolution' by explaining that "sometimes you have to get worse to get better"!

After the 'Ever More Spectacular Christmas' of 1983. The clean-up stepped up a gear, as any non-current merchandise was piled onto the counters and sold cheaply and the stockroom bins were scrubbed and consolidated. Despite new market rental charges appearing in the store trading analysis, a good Christmas had been followed by a bumper January. The Annual Inventory recorded that shrinkage was lower, partly as a result of accounting change by the new owners. For the first time stores were credited with 'markdown' if an item had to be reduced in price on central instructions or because it had become shop-soiled. All the signs were that annual profits would be significantly higher than they had been in January 1983.

Days later the Manager of Grafton Street, Dublin was summoned to a meeting. His boss did not want to discuss the Inventory result. He had dire news. The new owners had shown no respect for tradition, in closing 'Liverpool 1' and other hallowed pioneer stores that had opened before the Great War. Sadly the same fate awaited 'Store 31', which would close in April. The following weeks would be a testing time, when a Woolworth man could make or break his career.

It seems the Company had been sitting on the decision until after Inventory. News appeared days later in the house 'Management Focus' newspaper, and was confined to a single sentence. The Store Manager was promised a choice of a promotion, or a big 'package' (redundancy payment) and a terminal bonus if he could secure a smooth shutdown. To ease the exit enhanced severance packages would be available to the staff, who could also apply for jobs in neighbouring stores.

The Company had secured a remarkable £4.75 million for the remaining 24 years on the store's lease, but it was conditional on receiving vacant possession by May. Paternoster had a special fund for closures, which would give 50% of the value of stock recorded at Inventory to effect a complete clearance. Fixtures would be placed in storage and later used to fix up the older, smaller stores in the far flung reaches of the Republic.

Such was the veil of secrecy surrounding the closure that the news was not picked up by the Irish media until 5 April 1984 when the closing down signs went up in the windows at Grafton Street. It is possible that the left hand did not know what the right hand was doing, and that the Regional Manager, John Kennedy, genuinely did not know of the impending closure of all the remaining stores when the initial arrangements were made. But, by March 1984, the decision had clearly been taken.

Grafton Street closed without incident. Its long-serving staff closed the doors with great dignity, cheerful to the last. Its Manager moved north to Ulster, taking the helm at the store so good they named it twice (85 Derry/Londonderry in Ferryquaygate). The Managers of the other eighteen stores had little choice but to accept the Company's assurances that "we have no plans..." and the "the map we used was a British one...", hoping for the best while preparing for the worst. A frenzy of speculation in the Irish press caused disquiet among the staff, making their leadership task much more difficult for the next four long months. Operation Facelift took on overtones of the condemned man being forced to prepare his cell for the next occupant, while new inventory targets severely limited the funds available for stock purchases by the Buying Department above the Henry Street store.

The bomb finally dropped on 25 July 1984. Managers were told to make their way directly to Dublin for a meeting with Woolworth's Scotland, Ireland and North East Regional Manager, John Kennedy. He broke the news that poor trading had forced the Company to decide to pull out of the Irish Republic altogether. Every store would close and had already been sold. A press release to that effect would be issued in time for evening news bulletins. The Managers were instructed to return to their stores to inform their staff before the story broke on RTÉ.

The respected Irish historian Dr Barbara Walsh, who wrote the definitive history of the Company in Ireland, conducted extensive interviews in preparing her book When the shopping was good, WOOLWORTHS and the Irish Main Street (2011). She reports that "the occupants of the room were shocked to the core" by the news, made worse by accompanying PR spin which argued that poor profitability had caused the move. The Managers hotly disputed the Company's assertion that seven stores were loss making, seven were barely breaking even, one was profitable but in decline and just three offered the prospect of good returns in the future. Simply put, the cock-and-bull story did not line up with the annual results computed after the January Inventory that year.

The Irish media was critical of the decision by the Company's English bosses, which some considered a stab in the back or even a snub to the Irish Republic. The loss of 277 jobs came on a bad day. Administrators had been appointed to liquidate the Mirror Mirror fashion chain, which had a similar number of staff, and Travenol Laboratories had announced fifty further redundancies on top of ninety that were already in train. Press reports stated that the Woolworth staff, who had been gagged from speaking to the press, were understandably devastated.

By 1984 Woolworth's Personnel Department had plenty of experience closing stores. It had built a library of supporting materials. Regional Personnel Manager, Nigel Smith and his team of Area Personnel Officers had collated a small mountain of booklets and forms at the new Regional Office above store 793 Ormskirk, across the water in Lancashire, before heading en-masse for Ireland. The task was to prove much tougher than any of them expected. The Company had devised a method of paying extra to get everyone to leave quietly. The scheme, designed for the UK, had been tested in Grafton Street, Dublin and appeared to have worked well. It would prove a far less effective way of handling the other eighteen stores in the Republic.

Staff were approached individually rather than in groups. Each employee was invited to sign a 'compromise agreement' with the company. This offered up to four times the severance payment required by law with a much higher upper limit - but with conditions attached. The employee must sign a binding contract with Woolworth's, waiving any right to go to an Industrial Tribunal, acknolwedging the dismissal was 'fair' and promising not to discuss the settlement or any aspect of the redundancy with anyone, particularly colleagues and the media. Anyone who would not sign would get only the minimum. And anyone who did sign must understand that breach might be considered 'gross misconduct' and the Company might pursue legal action against them and seek to recover its costs on top of any payment that had been made.

It soon became clear that staff were in no mood for compromise. The Managers could not be bought off with promises of a move to Ulster or the UK, when their families were settled in Ireland and their children were at local schools. Everyone was outraged by the underhand way in which the Company had sold the stores from under them, skulking around with estate agents rather than consulting about how profitability could be improved.

On the face of it, the offer seemed generous. Ireland's Redundancy Payments Act, 1967 specified that employees with service of two years or more, who had not been made redundant for the previous four years, were entitled to half a week's pay for each year of service if aged 16 to 41, or a full week if they were older. It set a ceiling of twenty weeks pay. The average wage of a Woolworth Assistant stood at £100 a week, meaning the maximum statutory payment would have been £2,000. Woolworth offered two weeks pay per year served for all staff, however long they had served and whatever their age, with a ceiling of £17,000. To placate recent joiners the Company also promised a minimum of a month's wages at standard rate.

Any chance of gaining widespread agreement was undermined by crass errors in the briefing packs that the Company handed out, which had obviously been written for the UK. It noted that, as an exception to standard policy, the employee would be allowed to retain and redeem any unspent staff discount vouchers. It also promised that their Personnel Officer would try to find them a job in a neighbouring branch, and arrange for any extra travel costs to be reimbursed. As many staff observed, following a complete shutdown in the Republic the nearest Woolies stores to shop or work in would be north of the border in Ulster or across the Irish Sea in Douglas, Isle of Man or North West England.

One suspects that however generous the Company's offer had been, it would never been enough to compensate for the subterfuge that had preceeded it. On 27 July an article in the Irish Times headed "An end to the five cent store" reported "On two previous occasions this week Woolworths had issued categorical denials ... that it was contemplating the closure or sale of any of their outlets in the Republic". This only served to fan the flames.

As summer turned to autumn the acrimony behind the scenes spilled onto the salesfloors. On Tuesday 11 September the Connacht Sentinel led with the banner headline "Woolworths Closed Down by Dispute". It reported that staff in Galway City, who had never had a dispute before, were taking industrial action just three weeks before the store was due to close. They had enlisted the help of the Irish Distributive and Administrative Trade Union. The Union had said that " the staff were very bitter ... principally because of the manner in which the premises were sold", and that "there was no attempt made ... to protect staff jobs". Five other stores had joined the action.

In fact, behind the scenes Smith and his personnel team had been working tirelessly to secure jobs for the staff with Primark, the owners of the Penney's store that was to take on the Galway buidling, and with other employers across Ireland. But the lack of foresight by the people appointed by the Board to handle property disposals had left them in an unenviable negotiating position. It would have been easier to obtain commitments before the buildings were sold.

An Executive at the London Head Office ignored the prime directive of good public relations. Instead of "accentuating the positive" by highlighting the efforts that were being made for the staff, he decided to 'talk tough'. He told reporters that no more money would be forthcoming, continuing "the staff will not be paid while they are taking the present action. The objective is to carry out the closedown in Ireland in a reasonable and humane way. The present industrial action is prejudicing this objective." As if using language which could equally apply to cattle being sent to slaughter was not enough, the Woolworth Legal Team went further, threatening to go to Court to regain control of their stores. An order was duly granted, but never executed because events had moved on.

Fortunately the story was picked up for inclusion in the Board's 'Daily Cuttings' (a digest of any mention of the Company in the previous day's newpapers). The top brass hit the roof. This was far from the quiet, dignified exit they had requested. It was a shambles and a disgrace. Recriminations would follow, but for now they concluded that the only option was to buy their way out to make the problem go away, authorising the severance offer to be increased to five weeks pay for each year of service, to a maximum of £20,000.

As a result of the defiance of the Galway City team and the Irish Distributive and Administrative Trade Union, every employee across Ireland received more than originally intended, with many being paid more than double the amount the Company had set aside for them. Records show that the settlement was the highest ever achieved in any branch of the store-based Company through to its ultimate demise in 2009. It is little wonder that the Union recommended the offer and that the staff accepted it, turning their attention to the dreadful job of selling up and moving on.

But as many former Woolworth workers will tell you today, (whether American, Canadian, Spanish, Irish or British) life is about more than money, and some pain never really goes away. You cannot put a price on friendships or the love that so many people had shown for their employer over a lifetime's hard work. The hurt lives on, long after the fateful decision to close.

In the red or in the black? Could the Irish operation have been saved?

By way of a postscript, this section explores whether the analysis of trading prospects in the Republic was correct and what could have been done to fit the eighteen stores in to the dynamics of the new Woolworths.

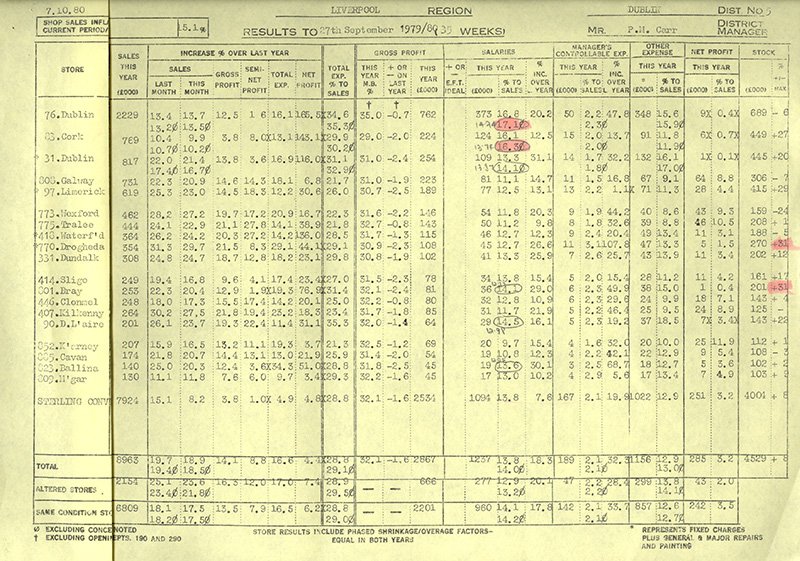

A review of the store trading analyses from the period shows that three stores were heavily loss-making in the early Eighties, and one other found itself regularly in the red. These were (in descending order of magnitude) Henry Street and Grafton Street in Dublin, Patrick Street in Cork and Lower George's Street in Dun Laoghaire. By contrast, even before any remedial actions, three stores were signifcantly beating the new management's profit targets.

- The large store in Galway City was achieving a net profit of 8.8% after all overheads (including Head Office costs, depreciations on the recent works etc) had been deducted, with semi-net profit of 14.3% to sales on a turnover of £1.7M.

- The medium-sized store in Tralee achieved a net profit of 10.5% wih a semi-net of almost 16% on a turnover of £900K

- the similarly-sized store in Wexford also turned a net profit of 9.6%, and a semi-net of 14.1% on its £900K turnover.

Each of these semi-net figures was significantly ahead of the 10% target set for the continuing stores in the UK, and each of the stores mentioned matched the size template shortly to be adopted as the ideal for a large branch. Limerick narrowly missed inclusion in the list above, achieving 9.8% semi-net profit on larger sales of £1.2M.

At the time standard policy for a Regional or District Manager reviewing the store trading reports was to compare and contrast the three or four best performers with the three or four worst, and to apply the best-practice from the top at the bottom. In the case of the stores in the Republic there was a howling difference between the best and worst performers - the successful stores had much higher productivity per employee, achieving a labour to sales ("cost-to-sell") ratio of less than 12%, while the loss-making branches had ratios of 16.6%, 16.1%, 14.1% and 13.3% respectively.

The challenge for their Managers should have been simple and unequivocal - either reduce the hours worked, for example by filling the counters quickly at night using cheaper student labour, making a commensurate reduction in daytime contracted hours through natural wastage, or boost sales by at least 30%. Do it now, do it consistently, and reap the rewards, or step aside and let someone else tackle it. If in doubt the Managers should have been sent to Woolco Newtownards in Ulster, where concern was expressed that the cost-to-sell never reached as high as just 7%! The gross margin in Cork also merited investigation. It was 2% lower than at any other store in the Republic. Each pound passing through its tills made tuppence less profit as a result.

Two other underlying causes in the Dublin City stores went unexamined. Firstly, the figures show that the popular restaurants in these stores were heavily loss-making. Much of the excess labour costs for the stores as a whole emanated from the food service operation. Not only were the restaurants inflating the labour costs, they were also delivering unacceptably low profit on the selling space, and should either have been closed or re-worked to improve productivity. Secondly, it was well known in the UK operation that a halo effect applied if one of two stores in a major town or city was closed, as trade transferred, making the surviving store much more profitable. The reality was that for many years the Grafton Street store had been retained for emotional and heritage reasons, and because of its fashionable address, while delivering only 35% of the sales and profit per foot achieved at Henry Street. Despite its Managers tightly controlling costs, it was still lost more money than the rest of the Irish operation combined. The dust should have been allowed to settle.

Had Grafton Street closed and the eighteen remaining stores focused on employee productivity, and Henry Street given up, say, a quarter of its floor space in a sub-let or concession (perhaps by closing its popular restaurant), the figures suggest that every Irish branch could have achieved a 10% semi-net profit by the end of 1985.

So how could the chain be described as loss-making?

It seems that two extra costs had been added into the calculations which did not appear on the store trading analysis reports. One was a charge for extraordinary losses made on currency fluctuations in the previous year, which it was assumed would happen each subsequent year. This seems wrong. It is generally accepted in accountancy circles that such variations tend to be balanced by gains over a longer period. The other was an exceptional charge applied to the accounts for 25 management grade personnel at the Castleton Central Accounting Office who were supposedly engaged solely in managing the paperwork related to the Irish stores, converting the values entered on every document prepared in-store from Irish pounds to sterling before they were entered into the systems, and handling accounting and payments for the 80% of the Irish range that was locally-sourced. These hidden costs may well have been genuine, but with imagination many cheaper and less labour-intensive approaches could have been found.

So was it all about asset-stripping the buildings?

Despite the prevailing view that the real reason for the shutdown in Ireland was the desire to liquidate the real-estate assets, it has to be noted that there were many more valuable and less profitable stores in the UK, and that an unusually high proportion of the Irish stores were either long-leasehold or had expired leases that were renewed year-to-year at market rate. It seems that the true reason was to reduce complexity. At a time of immense change, as store operations in the UK were computerised and the supply chain simplified, each systems project was significantly cheaper, and completed much more quickly without the complication of needing to accommodate 20,000 Ireland-only products and the differences in the currency, legislative framework and taxation in the Republic. At the time the Finance and Systems Director at Marylebone Road in London was a certain Geoffrey Mulcahy, who was building a reputation for getting things done by ruthlessly removing any potential barrier to progress. The approach served him well, and soon saw him rise to become MD at Woolworths, before stepping up to the exalted position of Chairman and CEO of the renamed parent company, Kingfisher plc.

Was there an alternative to shutdown while still pulling out of the Republic?

With hindsight perhaps the best option would have been to operate the Irish stores as a franchise. Given that most of their buying was done locally, fees could have been charged to licence the brand name, and UK buying power and volume discounts could have been enhanced by allowing the franchisee to cherry-pick the items they wanted from the British range. This would have worked particularly well for the new, best-selling Ladybird ranges which were just arriving on the shelves. These were mainly manufactured by Cooneen Textiles in Northern Ireland. Surplus stocks of Chad Valley toys were later sold wholesale to Irish retailers. The franchise concept may sound fanciful, but, for the record, in the 2000s Woolworths re-entered the Irish market precisely by licencing the Ladybird brand to a local entrepreneur and becoming a wholesale supplier.

Over time the franchise approach could have generated more cash than disposing of the property assets, and could have rewarded the Irish Woolworth with the same independence that New York had recently afforded to its long-time subsidiary in the UK.