Panorama

A century of pots and pans from F.W. Woolworth

The simple saucepan played a defining role in establishing F. W. Woolworth at the heart of the High Street. It helped the chain to prosper for five generations. This page tells the story of how Woolworths got the world cooking, with decently-made, mass-produced pots and pans. It also reveals how tastes, designs and manufacturing changed over that time.

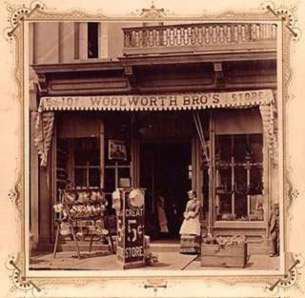

Frank Woolworth opened his first store in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, USA. Within weeks the humble saucepan had become one of his most profitable lines. The hole in the wall shop achieved enough turnover to persuade him to hire his brother Sumner to open a second branch in nearby Harrisburg.

His great grandson very kindly shared a picture of that store from the family album. It shows its frontage dominated by a bold display of pans. These were destined to become a microcosm of the whole Woolworth ethos. They were mass-produced yet stylish, well-made yet affordable, and above all were sold at the jaw-drop price of just 5¢, a quarter of the 20¢ price in most fancy department stores.

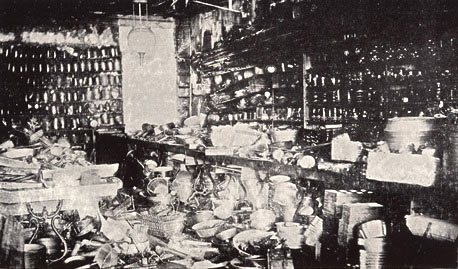

The first stores had makeshift counters. Their founders laid wooden planks across upturned packing cases, covering them with red cambric material to make sales tables. They believed that shoppers were only interested in the products and their ultra-low prices.

The counters were filled with ends-of-ranges which wholesalers in New York had cut to clear. These were supplemented with a selection of items which their former boss had agreed to supply from his Dry Goods Store in Watertown. Frank Woolworth's aspiration was to trace the best-selling items back to their manufacturers and buy direct.

The young merchant had the gift of the gab. He offered up-front payment in cash for goods, in exchange for a hefty discount. As his business grew he was able to place very large orders. He made it his mission to visit the factories and see how the goods were made. Often he was the first Buyer ever to do this, and impressed suppliers with his eye for detail, which allowed him to suggest ways in which they could boost efficiency, and still make a good profit, despite the low price he was prepared to pay.

In the early days Woolworth enlisted support from family members and former co-workers to expand the business. Rather than force everyone to work for him, once they had learnt the ropes, he allowed a measure of independence as they opened stores under their own names and formed a Buying Syndicate. Under the arrangement Frank sourced much of the range, boosting his buying power, which his 'friendly rivals' could then top up with items of their own. The consortium proved an effective way to expand rapidly, while spreading the capital outlay to avoid anyone having to borrow. The Syndicate was held together by Woolworth's larger than life personality, and his exceptional skill as a Buyer and Negotiator.

As he visited more factories his knowledge grew. He found his first European Buying Trips particularly informative. By 1890 many manufacturers had automated their production, achieving far greater levels of efficiency than anything he had seen in North America. He devised a three-pronged approach to persuade them to break with tradition and supply direct:

- up-front payment in cash

- handling the shipping through his own supply chain

- keeping the arrangement secret to avoid upsetting their regular clientele of wholesalers and agents

Intuition helped Woolworth to shape a very efficient supply chain. He ordered very large quantities to be sent by train to the nearest docks. Packaging was kept to a minimum. Everything went to New York CIty, where he set up a reshipping warehouse attached to his store in Sixth Avenue. Its staff collected the goods from the docks and sorted them into batches for each branch across North America. Quantities were defined in schedules which classified the stores into groups based on sales. The approach was ahead of its time. It minimised the on-cost, enabling the efficiency of the European factories to flow through to ultra-low prices on the shelves, while still achieving a margin of up to 40%.

After each overseas trip, as the goods raced off the shelves, Woolworth evangelised the mass-production techniques that he had seen to his indigenous suppliers. For those partners working exclusively for his Syndicate, he frequently financed the plant and equipment required to achieve the same efficiency, boosting sales and profit for both parties.

By 1905 the Syndicate had grown to almost 500 stores, spread right across the USA and Canada. As its buying power had grown, profit had risen rapidly. Fearing that they might be caught up in a spate of takeover battles, most members of the Syndicate took the opportunity to incorporate, selling shares to Store Managers and an inner circle of suppliers. Several of the leading vendors, who had grown rich on the strength of the huge volumes they had achieved with the Syndicate, jumped at the opportunity to take a stake. Their loyalty was rewarded with an invitation to tender for any new line that was required.

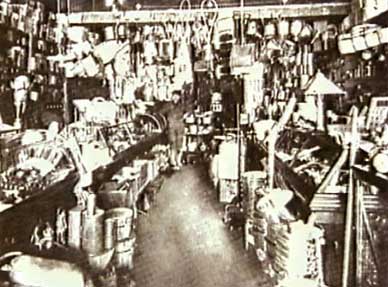

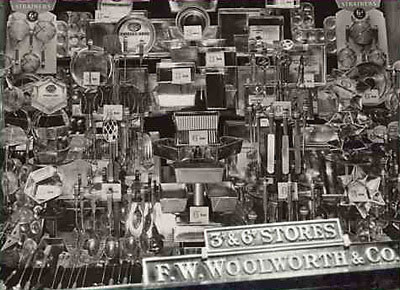

Saucepans and bakeware were given pride of place. Twice a year each store held a household week when the latest tinplated and cast iron pans were paraded in the windows and dominated the salesfloors. Some created a kitchen look by hanging the pans above the gangways.

From 1905 to 1909 the Founder put his second cousin, Fred Moore Woolworth, at the helm in Sixth Avenue. This gave his protégé control of the reshipping warehouse, and access to the paperwork showing where each line came from, which was a close-guarded secret. Frank was playing a long game, preparing the youngster for a much larger role.

The 1900s brought a subtle change to the Syndicate's formula. Woolworth had long believed that his stores did best in suburban locations and smaller market towns, but struggled to achieve the same profitability when paying the higher rent of prime city centre real estate. His cousin Seymour went against this perceived wisdom, opening a large "de-luxe" store in State Street, Chicago, Illinois, which was the City's prime shopping street. From the first day the store was rushed off its feet. It soon expanded to fill a whole city block. By upgrading the store environment, Knox had attracted more affluent City workers, who couldn't get enough of his pots and pans, besieging the Household Economy Department. This inspired his fellow Pioneers to copy the formula, and made Frank re-evaluate the offer, believing there was potential to upgrade and expand the range.

Believing they would be the next big thing, in secret he assembled a range of white enamel saucepans. For maximum impact he spread his orders around, buying just one or two types from each of his US factories until he had assembled a complete selection of shapes and sizes. He squirreled away huge quantities in the Reshipping Warehouse, where on a designated day cousin Fred distributed them to every branch.

Then, overnight, he placed the whole range on sale, nationwide. Bold signs announced 'Our new line of WHITE ENAMELWARE is now complete. Our highest price 10¢." Virtually all of the stock was sold out in a single day. In the months that followed the suppliers worked around the clock to satisfy the demand. The Syndicate had cornered the market.

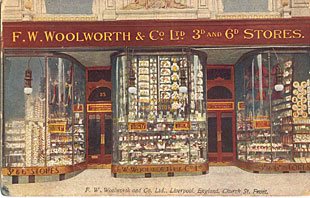

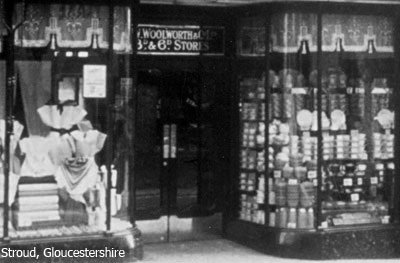

In 1909 Frank Woolworth embarked on a new adventure. For over ten years he had believed that a subsidiary would prosper in the British Isles. In 1896 he had noted in his diary "I believe that a good penny and sixpence store, run by a live Yankee would create a storm here," but had added "but maybe not." Each time Buying took him to Europe the idea resurfaced. Finally he deemed that the time had come. Despite the reservations of his senior management, he acted decisively. After press-ganging "volunteers", his invasion force set sail in May. In July 1909 he incorporated F. W. Woolworth & Co. Ltd. of London, and by November 5 his first store was ready to open its doors.

On opening day another Woolworth was at the helm. The Founder had co-opted his second cousin Fred Moore Woolworth as the first Managing Director. A former Superintendent from New York City, Byron De Witt Miller had assumed responsibility for Buying, alongside a local recuit, William Stephenson, who had joined from a supplier.

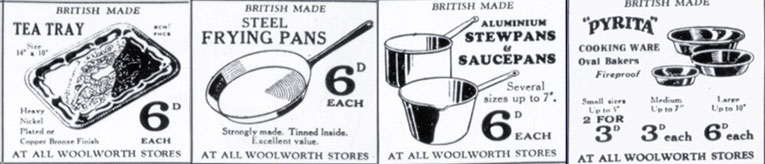

It had taken just five months to shape the branch in Church Street, Liverpool. Its range closely mirrored the offer in the USA, but was distinctly different. Virtually everything was British or European. And many items were just a penny, under half the US price. Miller and Stephenson had ruled out Frank's plan to ship goods from New York. Local factories were more efficient, achieving higher quality at a lower cost. So the two had systematically identified locally-made alternatives for over 2,000 lines. Saucepans were among the top sellers.

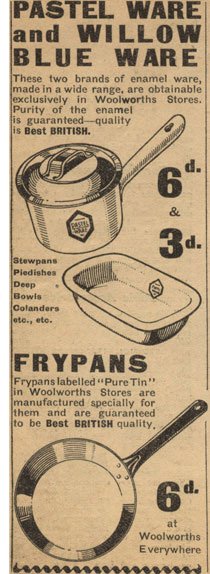

Kitchenware was a hit. The Buyers added value to the US offer. Their enamelled pans were larger and more substantial, but still only sixpence. Affluent housewives sampled the quality by buying an unlidden milkpan for threepence (1¼p, equivalent to £1.11 today). Many later returned to buy a full set of larger pans.

Other favourites included large, high class roasting pans and baking sheets, which were also just sixpence.

Capitalising on the high demand for the utensils, they were displayed at the back of the store, drawing customers in. A special maroon and gold 'Household & Kitchen Goods Dept.' sign marked the spot. The wily MD had chosen a location near the Tea Bar, and had told its staff to cook with the same pans.

Over its first twenty-five years the British Woolworth established itself as a phenomenon. It had five hundred outlets spanning the major High Streets of the UK and the Irish Free State, and added another every three days. These attracted twelve million shoppers a week, giving the chain huge buying power.

Suppliers had to absorb any rise in production costs to conform with the Company's sixpenny price limit, knowing that any item which did not offer a sufficient profit margin would be dropped. As rival retailers put prices up, Woolworth became ever more competitive, widening its appeal still further.

Keeping up to date was a key to success. Older lines were retired to make way for the latest innovations. For example the selection of tinware was increased and aluminium 'bellied' pans became fashionable. Earthenware oven-to-tableware was augmented with fashionable bakelite lines in bold, bright colours. The latest additions were often shown in the windows.

In 1936 factory costs started to rise as Britain re-armed. Suppliers soon found it impossible to make large nine and ten inch (22 -25 cm) pans for the 4d Wooolworth was prepared to pay. The Buyer sought guidance from the Board. They were unwilling to raise the limit like the American parent, and did not want to drop the larger sizes.

The Chairman proposed an alternative. The larger pans and their lids should be sold separately. Customers should be encouraged to buy a complete saucepan for a shilling (5p), but were under no obligation to buy a sixpenny lid.

This also applied to other ranges. Government super-tax was shown separately on gas lighters and playing cards, pushing the prices to a shilling and to 9d. Knitted woollen socks became "sixpence a foot".

Cartoonists sketched one-legged children hopping into class to recite the Woolies six times table. "6+6=6". The shilling price was still half the rate elsewhere. The outbreak of war ended the price limit. Soon saucepans became scarce at any price.

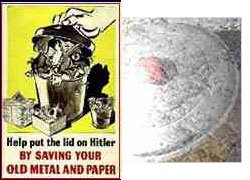

As the Country geared up for war, saucepan factories retooled to make aircraft parts. The resulting shortage was accentuated by a call for families to hand in surplus pans to be melted down. Many did their bit, believing the Spitfires flying overhead had once graced their stoves. Only later was it revealed that few pans had proved suitable.

When a store received saucepans it quickly drew a crowd. This had tragic consequences in New Cross. On Saturday 25 November 1944 a hundred people were queuing for pans when a V2 rocket struck the store. Just one person made it out alive.

Saucepans only finally began to return to the shelves in 1950. For five years after Victory most manufactured goods had been exported as the Government sought foreign exchange to pay off the loans which it had incurred in the dark days of the Battle of Britain.

The first stocks resembled those sold before the war, but at much higher prices. These had risen by up to 450%. For example kettles which had sold for sixpence in 1935 were two shillings and ninepence in 1950 (13¾p instead of 2½p). The decision to upgrade the range lay behind the particularly large increase.

Following a move favoured by the US parent, a few stores tested self-service operation in the late 1950s. For example Crawley, West Sussex, which had been a small village before the war was designated a "new town". Its store was relocated to much larger premises in the Queens Square shopping precinct, and adopted self-service. It proved a hit in the new town, but met with strong customer resistance elsewhere. Many people objected to serving themselves, highlighting the personal service which had often persuaded them to buy. The complained of long queues at the new cash desks. Executives also had doubts. They feared the layout encouraged shoplifting, and blocked any extension of the scheme. No-one wanted to rock the boat because by 1959 Woolworth had become the Country's largest retailer. Its shares topped the London Stock Market, out-performed only by the petro-chemical giant ICI.

Such caution would later have severe consequences. During the 1960s the lead eroded, as competition from younger, leaner firms rose. Success in the Fifties had been helped by Government regulations. Moves in the Sixties had the opposite effect. New legislation sought to drive down prices in the shops. As the law exempted Woolworth, it saw no need to act. Rivals were able to deploy self-service to reduce their operating costs, while the High Street giant maintained its tried and tested personal service counters, instead investing in ever larger stores. But the new giants like Castle Street, Shrewsbury, Shropshire appeared to be living in a time warp compared with their neighbours.

In 1964 a store-wide own brand called Winfield was introduced. For years each range had used its own house label, building respect and trust from shoppers. American Strategists forced a re-think. They sought to highlight "the value of the low entry price point range" with consistent packaging. After a promising start, Winfield lost its way. It made bottles of Sherry look the same as the weedkiller. Shoppers later told researchers that the livery meant "cheap and cheerful and made in Hong Kong".

The parent was also behind an even more controversial initiative. New York Executives insisted that London invest in Woolco out-of-town superstores, pioneering the concept in the UK. These were located on green or brown field sites, and offered large car parks and gigantic salesfloors of up to 100,000 square feet (9000m2). They carried the full High Street range, topped up by an extended range of food, fashions and homewares. Luxurious, more expensive saucepans from the leading brands nestled on the shelves alongside the own label lines drawn from the High Street. More adventuorous shoppers could even buy a fitted kitchen, or a stove at Woolco, and finance the deal with extended credit.

Much-publicized moves to land a man on the moon are said to have inspired a style revolution on the saucepan shelves of the late 1960s. NASA scientists had made Teflon as one of the many new materials anticipated by President John F. Kennedy. The non-stick coating soon earned a reputation for making cooking and washing up easier.

The Woolworth Buyer adopted the buzzwords of the age, describing his first non-stick utensils as "saucepans for the space age". The clever marketing persuaded shoppers to pay a little extra to become early-adopters.

But as the Seventies dawned the Buyer missed a trick. Rival chains like Marks and Spencer, Littlewoods and Timothy Whites all picked up on the increasing popularity of patterned, brightly enamelled pans with teflon linings, while Woolworth added the coating to its existing plain designs. The underlying cause of falling sales was only identified in 1972 after the Board ordered a review of the likely impact of Boots the Chemist's acquisition of Timothy Whites and its declared intent to build on the recent success of its cook shop. Saucepan orders were hurriedly altered to upgrade the premium range, as the drive to the bottom at the lowest possible price was replaced by a desire to become more aspirational.

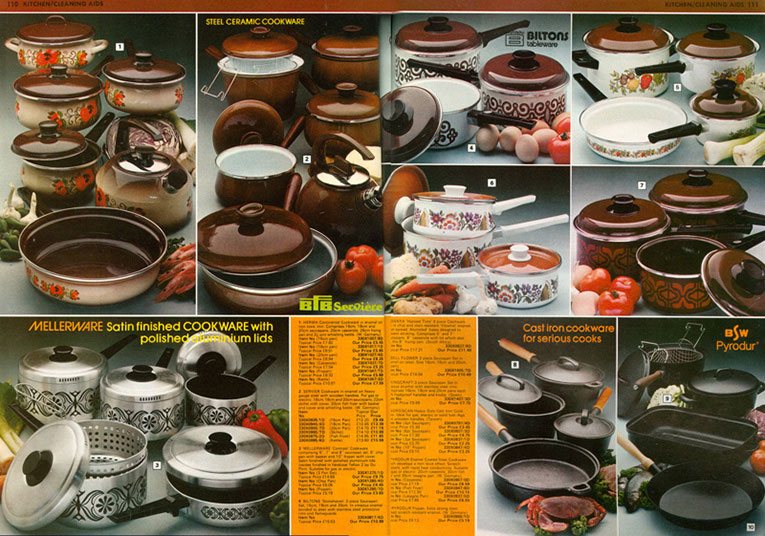

A series of new initiatives brought more stylish enamel pans in a number of patterns, and a range of kitchen electrical appliances. Big name brands were added, including Prestige, Tefal and Judge. Most were offered in sets at discounts of 25% or more below the manufacturer's recommended price, in a move calculated to undercut the competitors. A new catalogue store operation offered slightly higher discounts. Its catalogue gives a useful snapshot of the late 1970s range. The example shows that by the 1970s most saucepans were sourced from overseas. Four of the ten featured items were made in Germany, two in Spain, one in Taiwaan and one in South Africa, leaving just two that were British-made. In the late Seventies sales staged a recovery, driven primarily by extensive advertising on television, backed up by deep price cuts to win back custom.

In 1982 the British stores changed hands in a management buy-in. The new owners embarked on a major overhaul. Many lines were dropped in a move to build an authoritative offer in six key areas, including "Home, Kitchen and Garden".

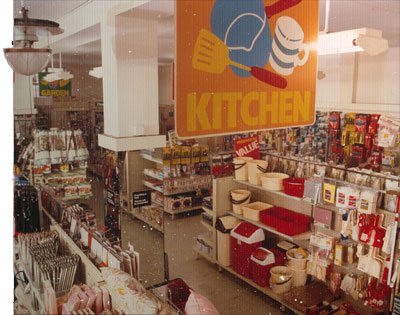

The Kitchen shop was identified as a key strength. It got a major makeover, with fashionable, colour co-ordinated products 'geared to Eighties living'. Designs were re-engineered. Saucepans were split into "good, better and best" models. The budget range, called "bellied pans" were non-stick, polished aluminium. 'Monarch' mid-priced saucepans were coated with cream enamel with a floral pattern. Brands like Tefal and Tower formed the 'best' selection and were keenly discounted.

The shopping environment in some stores was upgraded. Others made do with a lick of paint before displaying the new lines. The contrast between the refurbished and traditional stores was plain to see, particular in the branches that had retained their antique emergency gas lights.

As budgets were tight attention focused on the branches with the highest potential. As well as testing the new ranges, the first conversions also modelled pricing strategies to see which generated the most profit, and experimented with different layouts and shelving. The range was soon rolled out, while the refurbishment programme took much longer.

The hard-nosed approach drove rapid profit growth. The gains were shared between investors, acquisitions elsewhere in the Group and a modernisation programme in the High Street.

Competition grew in the 1990s. Wilkinsons expanded rapidly. The Sheffield firm's budget ranges were much cheaper than the Woolworth equivalents. Supermarkets also began to offer or broaden their home ranges. led by Tesco's 'Home & Wear'.

Kingfisher responded with an everyday low price initiative. Each operating company was encouraged to co-operate more closely with its suppliers to cut costs and improve value. The initiative, known as 'EDLP', sought to banish barely credible "half-price" offers in favour of everyday low prices.

This echoed the Founder's principles from the 1880s. The 5 & 10¢ business had generated huge profits by selling more for less. The Buyers had to follow the steps that Frank had trod a century earlier, examining the manufacturing process and eliminating anything which added cost but not value.

EDLP helped to win back trade. After a hiccup profit rocketed to over £100m in 1997. It seemed a new dog could learn old tricks!

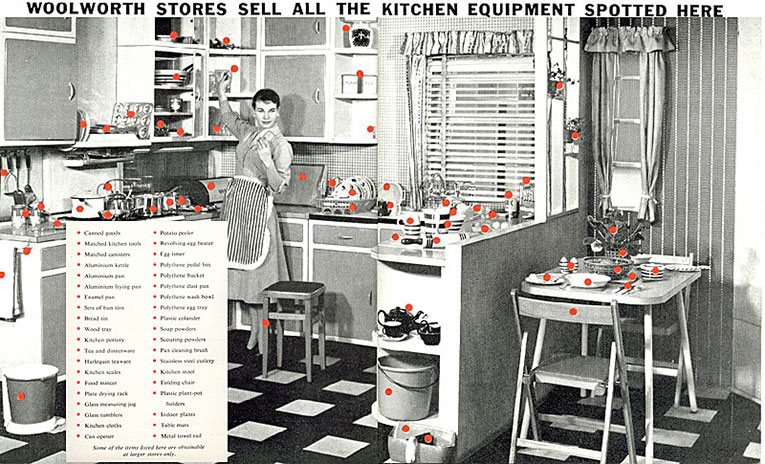

As the millennium approached work Executives worked on a new strategy for the High Street stores, fearing the fifteen year old trading format was getting tired. A key element of the makeover was a relaunch of the Kitchen Shop. The range was expanded and new tables and wooden shelf units were used to update the displays. Customers liked the change, although the move did not fully justify taking away space from other ranges. It proved more successful out-of-town, which formed another element of the new business plan. Big W boasted ample free parking, a broad range and a friendly atmosphere.

Implementation of the strategy was interrupted in 1999 when a merger between Kingfisher and Asda failed at the eleventh hour. Investors forced a major shake-up, ultimately leading to the break-up of the Group. Woolworths duly listed on the London Stock Exchange in Summer 2001.

The slow and painful separation process debilitated the business, prompting the departure of many Executives to roles elsewhere. This was compounded by the decision of the Group's new chairman, Gerald Corbett who had joined after a torrid time at the head of Railtrack, to bring in a new CEO from outside rather than pick any of the three seasoned MDs at Woolworths. Trevor Bish-Jones evangelised a major shake-up. He argued that the 'everybody's everyday store' approach was outdated, and that Woolworths should target a specific customer group. H opted to specialise in products for children under the banner 'Kids and Celebrations'. From 2002 onwards the importance of the Kitchen ranges started to diminish. As the stores were updated, the displays were demoted to the very back of the sales floor.

The new man also decided to change the price proposition, reducing the number of small items to make way for larger, more luxurious lines at higher prices. The goal was to deliver higher margins which would finance an enhanced store environment.

The new ideas were evaluated in Hemel Hempstead, Kettering and Market Harborough, before a more polished version transformed the South West London store in Kingston-upon-Thames.

Pans and cookware were given pride of place on the wall. Underlit floating shelves gave prominence to a new selection of small electric appliances.

The results in Kingston exceeded expectations. Over the next three years 150 further stores received the same treatment.

A new 'Cook!' range of saucepans with thick bases, the latest non-stick coating, glass lids and a polished finish, attracted the clientele of speciality shops. But the high prices put it out of reach of less affluent shoppers, who turned to Wilkinsons for something cheaper.

The up-market merchandise proved popular in bright modern stores like Bristol, Hartcliffe, but seemed incongruous in the many smaller stores which had not been modernised and were starting to deteriorate. Some loyal customers felt abandonned by the brand.

The CEO opted to invest in e-commerce rather than upgrade the small stores. They had to make do with an in-store ordering system. While strategically correct, this ignored the reputational damage that the delapidated state of the premises was causing. The high set-up costs online would need time to make a return, when action was overdue to arrest a steep decline in shopper numbers. Two million people a week had abandonned the chain since its demerger.

Finally, in a last ditch move, a new MD was headhunted from Asda. Tony Page set about restoring competitiveness and broadening Woolworths' appeal to the mass-market. He introduced a 'low entry price point' range at jaw-drop prices. The 'Worth-It!' lines quickly began to win back trade.

Between 2006 and 2008 a thousand WorthIt! lines built weekly sales of above £1m, dominating the chain's top seller list. Clever design meant the lines had higher than average margins thanks to good design and clever buying. Pleased with their purchases many WorthIt! saucepan customers also treated themselves to the occasional luxury from the fancy non-stocl Stainless Steel Cook! range.

Sadly Page's insight came too late to stop the rot as the Group's Wholesale Division demanded ever-more cash to fuel its growth. Just forty-two days after the cash ran out the stores vanished from the High Street.

Shortcuts to related Home, Kitchen and Garden content

The History of China and Glass at Woolworth

Thrift and economy - DIY at FWW

Blooming good - seeds, bulbs and plants