Leading lights

The history of bulbs, shades and electrical items at Woolworth's

This page celebrates two 'leading lights' who changed the world:

This page celebrates two 'leading lights' who changed the world:

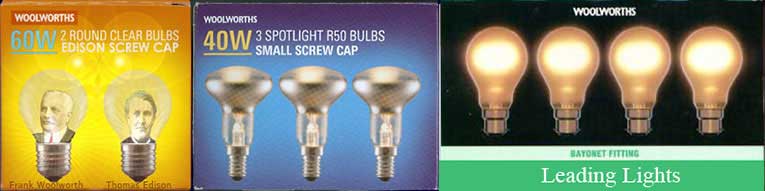

Frank Winfield Woolworth (1852-1919) evangelised factory mass-production. His 5 & 10¢ stores bought directly from manufacturers, pioneering a style of retailing that welcomed everyone, both rich and poor.

Thomas Alvar Edison (1847-1931) invented the gramophone, the incandescent light bulb, commercial power stations and the electric train. He was the ultimate inventor's inventor.

Edison patented his first light bulb in the same year that Woolworth opened his first store. The 5 & 10¢ was among the first to adopt electric lighting. The two men collaborated on several projects, as both the stores and the skyscraping Woolworth Building became showcases for technologies from Menlo Park.

Like many buildings of its time, the Great 5¢ Store in Lancaster store was lit by a single gas lamp. The globe hung at the centre of its ramshackle interior. Every early store sold gas burners and rings, globes and petal shades at prices of 5¢ and 10¢.

Woolworth was intrigued by news that Edison had patented a light bulb. He had already seen arc lighting on his buying trips to England, and knew of the (Humphrey) Davey Lamp and Sir Joseph Wilson Swan's filament bulbs. But now an American had forged ahead, becoming the talk of New York. He resolved to use the technology to set his stores apart. Soon his floors outshone the competition, while the windows, which were always elaborately dressed, became silent salesmen after dark. In the early 20th Century Woolworth 5 & 10¢s became a beacon of light in Main Streets across the USA.

By 1900, bright light shone from many Woolworth windows. Lancaster was singled out for special treatment. The original hole in the wall stores was replaced by a six floor skyscraper and was fitted with the best of everything. Its spacious mahogany-clad salesfloor was brightly illuminated with huge 150 watt bulbs in ornate glass dome shades when it was revealed in 1905.

Four years later Woolworth took the brand to the UK. Over the next decade, many of the eighty branches that opened were the first shops in town with bright electric lights, making them look much more modern than the competition.

The creativity of Edison's team at Menlo Park was legendary. So was their gift for marketing and promotion. Thanks to this self-publicity today most people believe that Edison invented the light bulb, rather than the British scientist Sir Joseph Wilson Swan, who had secured a patent for a filament bulb three years earlier. Back-chat was simply silenced when Edison bought Swan's business.

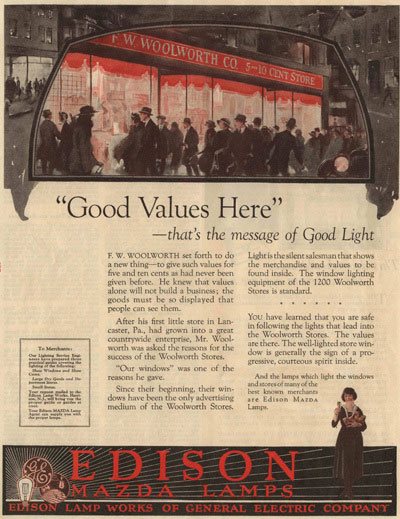

The inventor's flair for publicity led to a series of campaigns with Woolworth's. The 5&10¢ Founder loved gadgets and technology. Edison's General Electric Company gave special discounts as a quid-pro-quo for an endorsement which saw the retailer's stores feature in full page advertisements in leading journals for patented Mazda bulbs which gave a 'good light'.

This win-win led to a much larger project. Hearing of Woolworth's plan to construct the world's tallest building , Edison offered to provide the light and power. Plans for the 792 foot skyscraper in Broadway Place, New York included many of Edison's innovations.

Woolworth commissioned Cass Gilbert. He sent the eminent archiect to London to study the Houses of Parliament, which he considered the ultimate in style and taste. Gilbert's tower stood 792 feet above the sidewalk, with foundations to a depth of 121 feet. It had fifty-five floors, topped by a viewing platform, and two more below ground.

Woolworth loved the design and paid the full $13.5m building cost in cash, drawing from his banked store profits, and the proceeds of incorporating F.W. Woolworth & Co. in 1905 and selling some of its shares to Store Managers and friends.

This was no vanity project. The entrepeneur was determined to turn a profit. He established a separate company to oversee the project, appointing himself Executive Chairman of the Broadway Place Realty Corporation. He played a full, active part in the project, negotiating terms for most of the building materials, tracking progress and marketing the building to prospective tenants. He sought the best New York businesses, certain that they would pay a hefty premium to be able to say "our offices are in the tallest building on earth".

Foregoing his usual love of thrift and economy, Woolworth demanded nothing but the best, seeking both elegance and practicality. As New York had stretched skywards there had been scare stories of lifts tumbling to the ground and of power cuts leaving wealthy entrepreneurs stranded aloft. Woolworth turned to Edison for a solution. The inventor recommended that the building have its own pair of generating stations, housed in the sub-basement, each powered by two Corliss engines. The failsafe approach made the Building self-sufficient, with enough capacity to supply a city of fifty thousand souls.

Gilbert and his patron also worked with the Otis Company to design thirty express lifts with special safety brakes, air cushions and speed governors. Pre-publicity assured would-be tenants that this could halt a falling lift safely, proving the concept by placing a carton of eggs in a lift and setting it plummeting towards the ground. Despite the safety features the lifts were super-fast. Anyone stepping aboard in the Lobby could alight on the 55th Floor Viewing Platform under a minute later, hardly giving them time to exploit the on-board telephone!

By the time it opened every square inch of the massive building had a tenant. F.W. Woolworth Co. had occupied all of the 24th floor immediately below the tower, along with some of the floor below. The 24th had been built at double-height. It housed Frank's private office, known as the 'Empire Room', which was decorated in the Napoleonic style.

300 service personnel took care of maintenance and looked after the 15,000 people who worked there every day.

On 24 April 1913 Thomas Alvar Edison was a particularly prized guest at the grand opening of the Woolworth Building. Like all the attendees, to his surprise, he was taken to the banqueting suite by candlelight, as the tower stood in semi-darkness. The reasoning soon became clear. Woolworth, ever the showman, had planned a spectacular inauguration, assisted by the highest in the land, the US President Woodrow Wilson. At the designated hour the Commander-in-Chief flicked a switch in the Oval Office down the coast in Washington DC, instantly illuminating the tower from top to bottom with Edison's magnificent electric lamps. The spectacle was enough to bring traffic to a halt as it beamed out across the night sky, and was greeted with rapturous applause. Edison later described the day when Woolworth had planned the event as "a light bulb moment"!

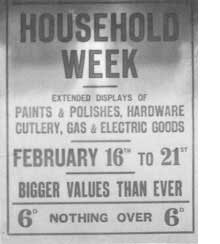

In the British stores few customers had the benefit of electric light at home until the 1930s. Most houses and tenements were illuminated by gas and heated by a coal fire. Woolworth's Household Economy Department had a selection of accessories to keep everything running smoothly. As well as coal shovels and scuttles, its gas range included rubber hoses, copper tubing, gas taps and keys. The best sellers were porcelain domed sixpenny lampshades in various styles, some for ceiling roses and others for table lamps.

Working people had much less disposable income before World War II than they do today. When it became available only a few families in poorer areas chose to install electricity. As a result while Woolworth stores in affluent suburbs sold thousands of plugs, sockets and lightbulbs like their cousins in the USA, others sold next-to-none, but continued to do a roaring trade on the older gas fittings.

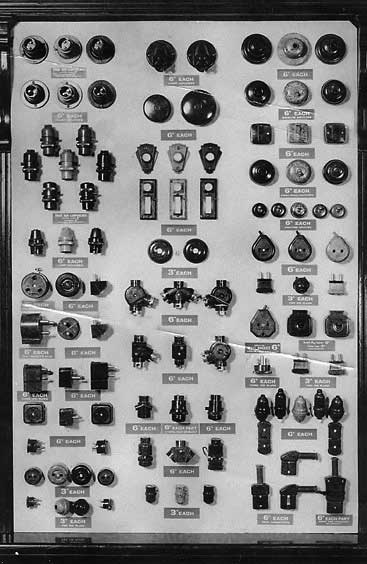

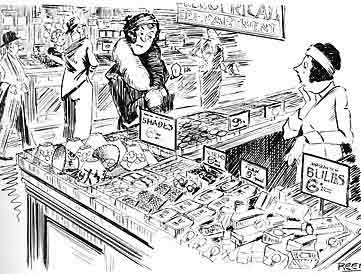

In the 1930s Woolworth made the case for electricity in the windows of its larger stores like London Road, Liverpool, while also promoting its gas accessories. The emergence of bakelite, an early plastic, encouraged the Buyer to push harder as the decade continued. He had cornered the market in electrical fittings, including switches, plugs and adaptors, made from the new wonder material, which offered a high margin despite its sixpenny price being just a third of the rate charged elsewhere. Working with two key suppliers, Ward and Goldstone and HH Electrical, he gave away leaflets promoting the range, and sold little booklets showing more ambitious shoppers how they could wire their own plugs and install their own lights and switches.

At the time Bakelite was revolutionary. For the first time chemists had devised a material which could be shaped and coloured when molten, and would dry completely solid, smooth and rubust. It could withstand knocks and scrapes and generally would not break unless it fell onto a stone floor with considerable force. As well as the switches and sockets, presented in its natural dark brown colour, the material was used to create best-selling, brightly coloured oven-to-tableware and a range of remarkably elegant costume jewellery.

A few homes built in the 1930s still have bakelite door handles, and may even have the odd original light switch or batten lampholder. If the material got warm, as lampholders did when the bulb stayed lit all evening, it gave off a slightly fishy smell. Later the pong was enough to persuade many people to upgrade to modern white plastic.

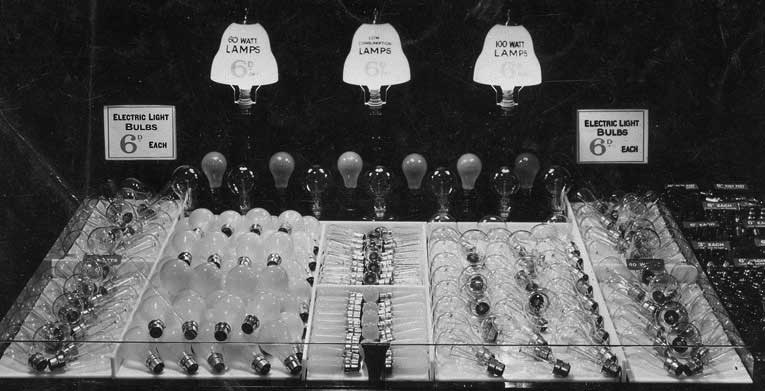

Back in the 1930s items were sold loose, from flat displays kept tidy by glass dividers. Not packaging things made them cheaper. The original 5¢ & 10¢ stores wrapped goods in newspaper, but as the company grew, it kept a stock of bleached paper bags available on demand. Most women took their own bags when they went shopping, and rarely asked for an item to be wrapped.

Stores gave some of their wall space to non-selling displays, which were used to showcase the latest lines. The electrical suppliers provided sample boards of their best items, along with prices. They recommended that customers buy a threepenny 'how to' book. It gave simple, step-by-step installation instructions.

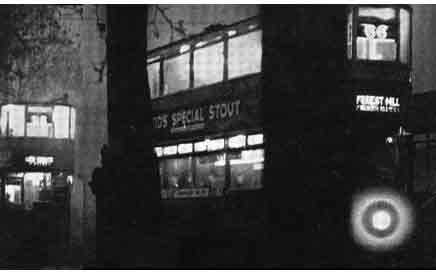

This Woolworth torch played a special part in helping East Enders through the London Blitz.

During the blackout its owner carefully covered the lens with her fingers until just a single ray of light shone out. She then pointed it up onto the power lines that supplied the tram, so that she could gingerly swap the conductor rod onto the down line for the return journey.

Many years later she gave the torch to the Museum, still fully working at the ripe old age of sixty. She noted "it was only sixpence, but this torch deserves a medal for 'service to London".

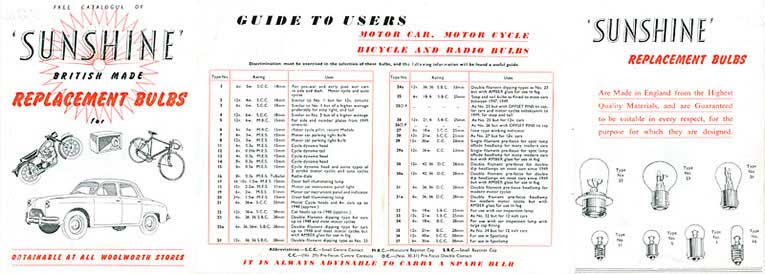

The electrical range was extended after World War II. The Buyer was no longer constrained by the strict sixpenny price limit of earlier times and began to source more luxurious lines. By 1952 as well as a dozen different types of Sunshine Lamp branded bulbs, he had introduced electric flex for fourpence a yard (2p per metre) luxury lampshades at prices up to five shillings (25p), and fancy table lamps for 5s 9d (29p).

Fixtures were tailor-made to suit the needs of the new lines. Lighting canopies were installed at the back of most salesfloors creating an illuminated display of the shades and fittings. Flex dispensers were altogether more practical, accommodating the large reels neatly, along with scissors and a ruler.

As household incomes rose, people began to buy or rent television sets. Many relied on Woolworth to supply flex to extend the lead to the nearest socket and insultating tape to attach it, along with a two- or three-way adapter. Some also splashed out on a long piece of coaxial cable to connect an aerial in the loft. Jo-Jo and extension lead reels had yet to be invented, and the danger of joining electric cables with sticky tape was not fully appreciated.

The range of bulbs was enlarged as customers became more affluent. Where once most shoppers had lit their homes by gas, now as well as bulbs for lighting, Woolworth also sold for replacement bulbs for cars and motorbikes, as well as radios and other household appliances.

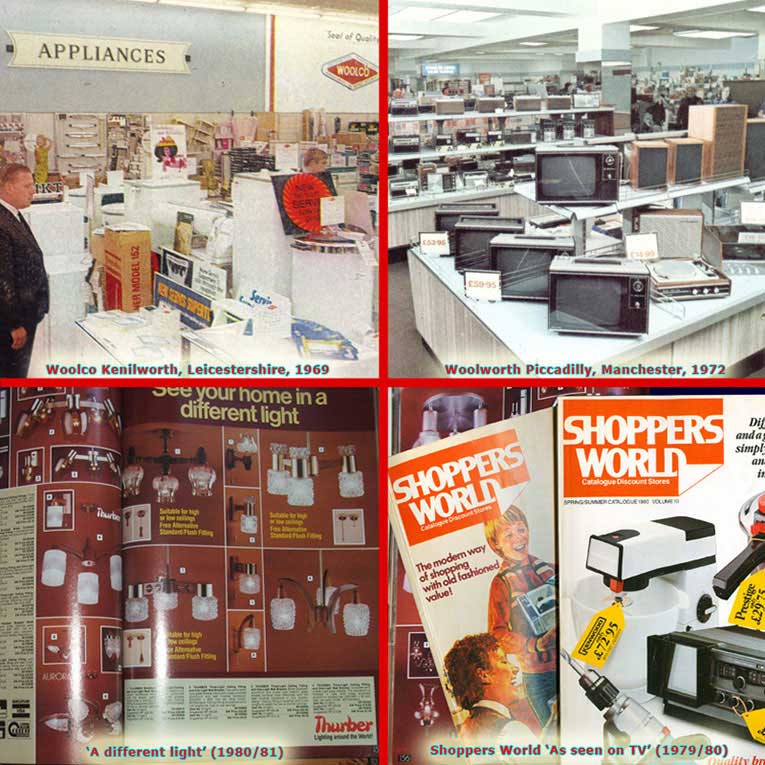

A decade later the chain added appliances to its range. The fires, hairdryers, power tools and striplights were sold under a new own-label called Winfield. Larger branches also carried branded televisions, washing machines and large domestic appliances. During the 1970s the range was also sold through a new venture, the Shoppers World catalogue.

Working practices struggled to keep pace with the new ranges. Until 1975 many branches continued to operate a personal service model, taking payment at each counter, long after others had adopted self-service.

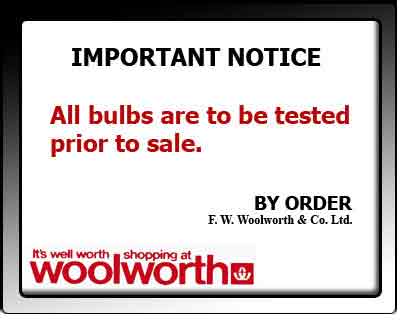

Customers also found it quaint that the staff had to test every bulb in a baton lampholder before it was sold. To enable this every lamp box had an open end.

The bizarre practice was finally dropped after the business changed hands in 1982. While remarkably there had been no reports of electrocutions on the live terminals over the previous half-century, the new owners deemed it a hazard under the 1974 Health and Safety at Work Act.

Woolworth struggled in the 1970s. Increased competition, price inflation and industrial unrest all contibuted to its problems, along with self-inflicted wounds. Diversification in North America failed to deliver the expected returns, causing profit to fall. This was accentuated by mediocre results in Britain and Ireland. Faced with mounting debts, in 1982 it accepted a management buy-in offer from a local consortium which wanted to take over the chain's operations in the British Isles.

The new owners had spotted the profit potential of the recent acquisition of B&Q, as well as hidden value in the freehold property portfolio. It embarked on a major shake-up, closing the largest stores in City Centres and selling the buildings, along with Woolco and Shoppers World, and reshaping the small and medium branches. The moves restored Woolworth's fortunes in the High Street in parallel with establishing a diverse and profitable portfolio of other retail businesses across the world.

As the average store size fell, B&Q became the main group outlet for DIY, establishing itself as the dominant player in the market. Another acquisition, Comet, took on the electrical appliances.

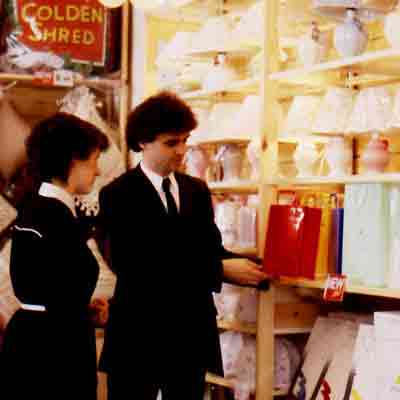

In 1984-5 a new look was trialled in the High Street. Lighting, electrical accessories and lampshades featured strongly. Sales and profits exceeded their target, but did not achieve a sufficient return to justify refurbishing the outdated lighting canopies across the chain, so the range was adjusted to concentrate on table lamps and shades when the new formula was adopted nationally.

The light bulb and accessory selection was updated. Targeted promotions helped the stores to sell over a million multipacks of four bulbs for 99p each autumn. The 60 watt pack sold more than the combined totals of the 40W and 100W variants. At the time shoppers also stocked up on 3 packs of plugs, ready for any gadgets they might buy, A decade later plug sales suddenly collapsed. A new European law was to blame. It required every appliance to be fitted with the correct plug and fuse when it was made. This also brought a craze for brightly coloured plugs to an end. For a number of years shoppers had chosen bright red ones, and had carried the styling over to their sockets and light switches. Red outsold all of the other colours together, although it never matched the sales of the standard white.

The Buyer also worked with Duracell and Ever Ready on a campaign to get shoppers to trade up from traditional zinc carbon to alkaline batteries, establishing the chain as the market leader for these high margin lines. Shoppers often wondered why inner city stores stamped their name and address on every packet, guessing it might be an attempt to gain repeat business, when in reality the move had been recommended by the police to make it easier to trace the source of thousands of abnormally cheap batteries which were being sold on market stalls.

The restyling quickly began to boost sales and profits. The trading results were greeted with plaudits for the Board of Directors and a CBE for the highly-effective Managing Director, Mair Barnes, who went on to receive a coveted Business Woman of the Year award.

The Prime Minister, The Rt. Hon. Margaret Thatcher, PC MP, supported a Barnes initiative called "Young Leaders of the Future". The PM drew a crowd each time she visited her local Woolies in Grantham, Lincolnshire. On one trip she was snapped buying multipack bulbs and top-ups for her hosiery drawer.

As the trading environment became more competitive in the 1990s, the Commercial Director, Rob Cissell, slashed Home Range prices in branches that were going head-to-head with Wilkinsons. The move soon proved that the threat could be contained.

The tough market forced tight buying discipline as Buyers sought ways of boosting margins while holding or cutting prices. By redesigning items to allow them to be made more cheaply, market share was maintained across the electrical range. In the late 1990s supermarkets began to target everyday essentials like light bulbs. While they had sold the range for many years, until this point they had relied on the convenience of being able to pick up a pack with the weekly shop. When they began to compete on price, launching strong promotions of their own, Woolworths had to raise its game. For years sales had been impacted by erratic availability on the shelves. Systems were upgraded to tackle this, with a multi-million pound investment in EPOS scanning technology. The software replenishment the stock automatically. It also introduced multibuy and linksave light bulb promotions at the till, outpacing the grocers. The battle had been won, but the war raged on.

Under Kingfisher successive generations of Executives had proved that it was possible to face new entrants to the market head-on, and to maintain or even boost sales in the High Street store's chosen markets. But the base of experience began to dwindle after external events forced a break-up of the Group and Woolworths' separation as an independent listed business.

The supermarkets were quick to poach disaffected Buyers who felt uneasy at the turn of events. Armed with new knowledge about tactics and margins the grocers were able to accelerate their push into general merchandise and target their efforts more effectively. The shake-up at Woolworths stretched right to the top, with both the role of Chairman and of Chief Executive given to outsiders with very different ideas about the future direction of the High Street stores. They believed that it would be better to specialise further, becoming famous as a destination shop for mums and children, rather than battling to remain an everyday store for everyone.

To effect the plan they launched a new strategy, which extended the displays of clothes, toys, cards and entertainment and severely pruned the home ranges. The product mix of what remained was adapted to include more expensive lines like computers, telephone accessories and multi-way extension sockets, selling at higher price points, and eliminating most of the cheap accessories. The style and convenience appealed to Mums, but had little of relevance for older people or those tackling DIY projects. Men abandonned the stores in droves, visiting only as 'Dad' on family shopping trips.

After four years when electrical sales fell dramatically, and profit plunged across the store, a new MD was appointed who quickly began to stop the rot. As a shopper Tony Page had been a fan of the stores, and had been saddened to see them lose their way. He challenged his team to improve availability, noting that in recent times he had consistently been unable to buy the light bulb he was shopping for. He also shaped a new value range which he hoped would restore the traditional strength of the home ranges and 'outshine' the competition. The result was WorthIt!, a range of basic, mass-produced, everyday items at rock bottom prices. The selection included a 20p light bulb, in real terms the lowest price in 98 years, and a variety of power tools and home appliances for £5 per piece.

Such was the success of the range that it attracted attention from a surprising quarter. The environmental lobbying group Greenpeace besieged the company's offices in Marylebone Road, demanding to know why inefficient incandescent lightbulbs were being offered so cheaply. They followed this up with a spoof commercial on the Internet, sending up the retailer's lovable Wooly and Worth brand characters as being so idiotic that they were endangering the planet.

The affair reminded customers that the firm stocked bulbs and also provided a platform to expose the barriers to selling environmentally-friendly items cheaply. The European Community did not permit 'green' bulbs to be imported from the Far East, which made the technology too expensive for poorer families. The furore resulted in a change in the law, achieved largely by the lobbying power of Greenpeace, and saw Woolworths sell more than a million 11W WorthIt! light bulbs for just 50p each, a reduction of 80% on the prevailing price at the time.

In 2007, for the first time since demerger, customer traffic increased and sales of accessories started to grow again. Sadly it was too late. Growing losses and burgeoning debts meant the business was unable to follow through on the green shoots of recovery. Unable to persuade its bankers to provide additional funding during the Credit Crunch, the entire Woolworths Group collapsed into Administration shortly before Christmas 2008. The High Street stores put the lights out for the last time just forty-one days later.

Today in some small local High Streets there is nowhere to buy a light bulb. Supermarkets have gained the leading market share of batteries as other retailers compete to fill the gap that Woolworths stores have left. Around Britain one by one the long-life light bulbs supplied by the High Street chain are going out, having lived out their ten year guarantees. Now shoppers will have to go to any of 630 German stores, the new chains in either Austria or Poland or all the way to Mexico, Jamaica or Zimbabwe if they want the replacement to bear the cherished Woolworth logo. Let's hope that before long you'll be able to buy them at a Woolies GmbH store in the UK - you can get bet their bulbs will be amazing value for money!

Shortcuts to related Home, Kitchen and Garden content

The History of China and Glass at Woolworth

Thrift and economy - DIY at FWW

Blooming good - seeds, bulbs and plants