China and Glass at Woolworths

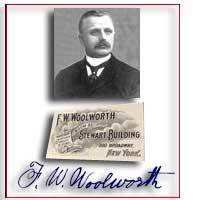

There were many china and glass items in the original Woolworth stores in Utica, New York and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The founder, Frank Woolworth, was among the first to embrace factory mass production to drive down manufacturing costs, so that he could offer well-made items at a fraction of the previous price. The formula caught the imagination of shoppers and helped Woolworth's to grow and prosper in North America.

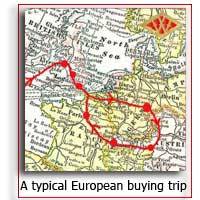

As others embraced the 5 & 10¢ Store idea, Woolworth established a Syndicate with family members and former co-workers, and supplied them with goods. He tracked his products to their source, buying direct from the factories. This took him to Europe, where manufacturing was more advanced. He visited twice a year from 1890 onwards, buying china from the English potteries in Hanley and Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire, before heading to London for paper products, and on to Europe for Toys, Decorations and Novelties.

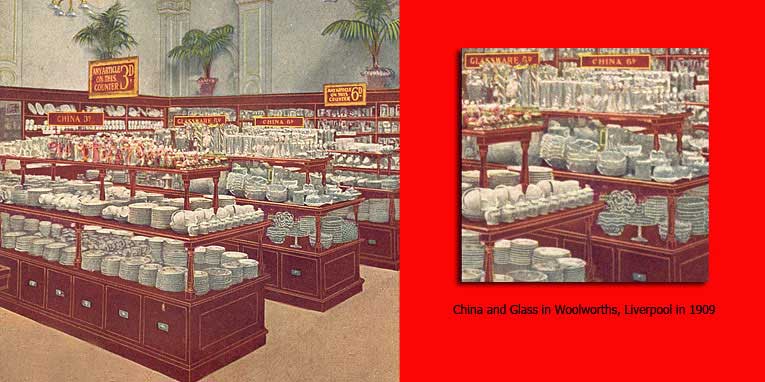

The European luxuries gave Woolworth an edge, which kept his stores ahead. The buying trips also inspired the first openings overseas as the first Threepenny and Sixpenny Store opened in Liverpool, England in 1909.

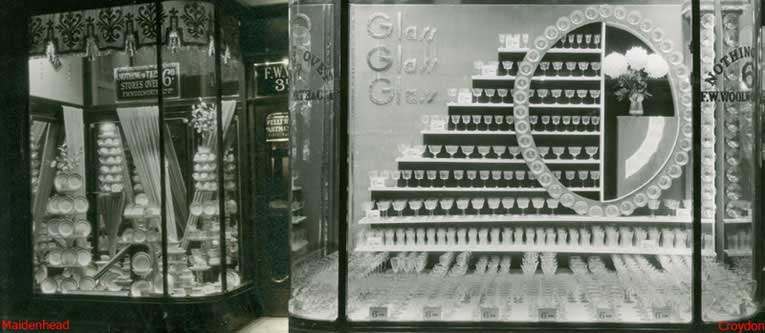

By the turn of the twentieth century china and glass had earnt pride of place in the largest 5 & 10¢s. The flagship in Lancaster had elaborate displays and sold thousands of pieces daily.

The huge turnover was powered by a reshipping warehouse in New York. It unpacked and distributed huge crates of crockery and glassware across the Syndicate, which spanned most US States and the Englsh-speaking Provinces of Canada.

The chain had found a great pattern for growth, Items retailing for its self-imposed 10¢ maximum typically cost just 3¢ to buy and ship to the store. With such a high margin Woolworth could afford to take risks, experimenting with ultra-modern brightly-coloured designs along with more traditional patterns. It also tried new shapes and some items which were principally decorative rather than functional. Soon it was doing a roaring trade on fancy-shaped vases in a rainbow of colours.

As the 5 & 10¢ grew, Frank hired an Assistant in New York, but continued to do all of the overseas buying. He was a poor sailor and found the sea crossing difficult. He followed the Blue Riband route from New York and Liverpool. Upon landing he had to rely on trains and horse-drawn carriages to cross Europe. When they became available, he bought a car in Paris and retained a chauffeur for his trips.

Suppliers found the entrepreneur friendly and affable, appreciating his win-win negotiating style. They particularly admired his limousine, which symbolised his success.

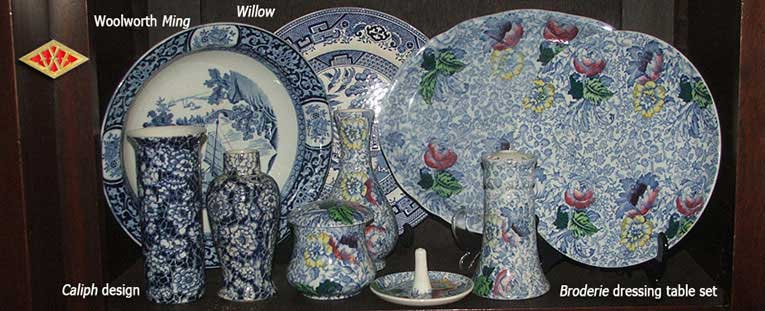

Frank sought a supplier for Willow pattern china, which was popular at home. He chose some bone china lines, but opted mainly for brightly-glazed earthenware. He also picked 'Fibre' as an exclusive. It had a deep blue pattern on a white base. The English design, with its 'Woolworth' or 'Imperial Woolworth' backstamp, proved a hit, particularly in Canada. The success made it a natural choice as one of the prime ranges in Liverpool when he took the brand to the UK some years later.

Many of the Woolworth china items sold for just threepence (UK) or five cents (USA), the equivalent to around one pound, one euro or $1.20 today. Buyers were instructed to carry any pattern they chose for an extended period. This gave customers time to build a set a piece at a time. Occasional new pieces were added to established ranges to attract repeat business. For example cream jugs complemented the original milk jugs, and large oval serving dishes and bread and butter plates gave extra spice to the Fibre range. These adaptations illustrate Woolworth's flair for marketing.

Frank's early Buying Trips to Europe were to have a profound and unexpected impact when the British Company opened. He had been impressed by a particular clerk who he had dealt with regularly in the Potteries, and head-hunted William Lawrence Stephenson, to be the sole British Director, and its Head of Buying as he planned the Liverpool store.

Stephenson provided Woolworth with an instant answer to press criticism of his "American invasion". The Founder assured journalists that the Yorkshireman would be the first of many local people that he would engage. All would join 'on the ground floor' to learn the ropes and work their way up.

The new recruit brought a deep knowledge of the local china and glass industry, and much more besides. He emerged as the natural successor to Fred Woolworth in 1923, and went on to build the F.W. Woolworth & Co. Ltd. 3d and 6d Stores from 120 to 768 branches before World War II, establishing it as the UK's most profitable retailer.

Woolworth's Buyers established a rapport with the Staffordshire potteries, welcoming new patterns and product ideas. A supply contract brought the right to 'try-out' any new line that met the basic rules in a small number of stores. Store Managers fought to be chosen for try-outs, knowing that these could be very lucrative. To be considered they had to ensure that staff completed special paperwork on sales and customer reaction and passed it up the line quickly. This gave both the Buyer and the Supplier a rapid insight into the potential, helping them to tune the colour, styling and price and try again until a winning formula was found. Although bureaucratic, the 'Woolworth system' set the retailer apart. It operated at such pace that, once chosen, a winning line could be placed on sale in every branch across the British Isles within a fortnight.

Fred Woolworth expected his Buyers to maintain a vibrant threepenny offer, not just focus on sixpenny line, saying "we give great value and we encourage people to trade up".

When Stephenson took the helm, he was equally demanding. He shared his experience of driving a hard bargain with Buyers like Charles McCarthy. For example the threepenny range could include slight seconds of larger items, or help suppliers to clear lumpy stocks of other people's luxury lines.

By the Thirties McCarthy knew that the very mention of Bakelite could draw a discount on crockery from some suppliers, even though he had only ever stocked a few beakers and some oven-to-tableware in the new wonder material.

The Thirties became a golden age for Woolworth. It achieved the nirvana of a "virtuous circle" in today's retail jargon. Its sheer scale drove prices down, generating enough profit to double the size of the chain to 750 outlets, which in turn boosted its scale still further. As inflation began to rise in the late 1930s, rivals began to put their prices up. Woolworth was ruthless in resisting any such move. It announced it had dropped a few lines and even a supplier in a bid to show its price limit was sacroscant, and it intended to keep its vendors lean and mean.

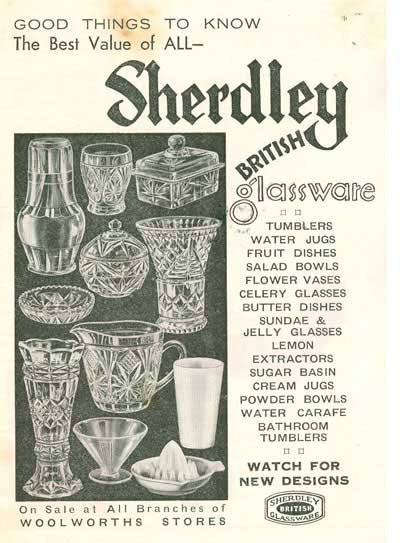

On a happier note, with value to boast about, it invested in fancy pictorial price signs for its best sellers, printing in colour for the first time. It also launched Good Things To Know, a threepenny lifestyle magazine, devoted to its ranges and how to use them. Suppliers competed for the best advertising space, knowing this would boost their sales.

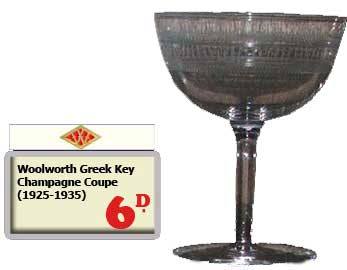

To complement the displays of china, F. W. Woolworth stores stocked a comprehensive range of glassware. The firm commissioned its own designs and had them mass-produced, thousands or sometimes millions of times. Some were lead crystal with ornate patterns, while others were more basic. The best selling sixpenny lines were jugs and tumblers, while threepence was enough for a fancy wine glass or a simple vase.

In the 21st Century, some of those best sellers appear regularly at Antique Fairs. Wine glasses in the popular Greek Key pattern sometimes fetch £5 each, while the rarity of the matching champagne coupe has driven the price to collectors above £20. The 'sixpenny special', which was only ever offered for sale on Saturdays, certainly lived up to its billing !

Inflation and shortages after the outbreak of World War II forced a major shake-up. Prices could no longer be held down, so the sixpenny limit was abandonned in 1940. A new directive from the Government required that everything that factories made must have a practical purpose; at a stroke this eliminated ornaments and put the popular range of vases in peril. However keen the suppliers were to comply, they could not obtain new moulds as the makers had been moved onto the war effort. A workaround was needed. Flower vase designs from before the War were reclassified as serving utensils, by adding the word 'CELERY' to the backstamp, while fancy candlesticks provided essential lighting in Air Raid Shelters.

With the shelves in-store depleted, every consignment sold out quickly, irrespective of its declared purpose. Whenever a rare item arrived, the news spread like wildfire, attracting a long queue until every last piece was gone.

The shortages continued long after the Allied victory in 1945. Rather than releasing goods back to the shops, a Government edict directed them abroad, and limited the quantities of foreign-made lines that could be imported to pre-war levels. The well-meaning policies aimed to earn foreign exchange to help pay down the huge debts that had been incurred to fight the World War. With new leaders at the helm, the Woolworth Buyers abandonned the longstanding policy of passive compliance with such red-tape, instead working around the restrictions to get the counters filled back up. The ruse involved the branch in Henry Street, Dublin. The Republic of Ireland had been neutral during the War. Its businesses were free to buy what they wanted from any source they chose, and crucially also had unrestricted free trade with the UK and vice-versa. So the Buyers ordered goods to be sent in bulk to Dublin. Its staff sent them on to branches across Ulster and the UK Mainland, in quantities set by the Buyer. The prices on the shelves reflected the increased handling costs so that margins were maintained, but, with most competitors' shelves severely depleted, customers shopped anyway, considering the premium a small price to pay.

The Buyers wanted more space to meet demand. They achieved this by building upwards. New rising shelves above the main display began to appear in 1948. These projected from the flat tabletop of the counter, taking an example of each item up to eye level, making it easier for the customer to examine.

Prices had risen six fold over a decade. Some sixpenny (2½p) lines from 1938, were three shillings and sixpence (17½p) in 1948.

Without a price limit the structure of the range had begun to change, as items were sold together in sets rather than separately, like a sugar bowl and cream jug set for five and sixpence (27½p).

The well-filled counters brought rapid sales growth between 1948 and 1952. Woolworth had raced ahead of its competitors by recovering more quickly after the War.

As the 1950s continued, British life started to return to normal. As rivals recovered, Woolworth's Buyers sought new ways to stay ahead. With household incomes rising they began to add stylish and aspirational china and glassware.

Finding little innovation from existing suppliers, the Buyer cast the net wider. He toured Art Colleges and Polytechnics in search of young talent who understood and embraced much-vaunted new production capabilities. The Government's Board of Trade had invested in technology which would allow transfers to be glazed onto plates, rather than each having to be hand-painted. The Buyer believed that this could cut the cost of making things and would allow him to risk vivid new colourful patterns and bolder designs on some of his crockery.

He was impressed with a number of students, including a young designer called Enid Seeney who had taken up a job at Ridgeways, an established supplier. The Buyer offered to buy several of Seeney's more conservative designs to test in-store. He expected a smile and a thank-you, and was taken aback when she challenged his selections, asking why he had passed over her best design, which she called Homemaker. Despite considering the black and white pattern too dull, he admired the spirit of its designer. On the spot he placed a small order and promised to see which of them was right by testing the design "in the real world". The Buyer later said that he had never been so glad to be proved wrong; "I freely admit it was Miss Seeney's arm-twisting that pushed me into the best decision of my career."

Enid Seeney also returned to the subject, contributing to a 21st Century documentary video about Homemaker. She revealed that shortly after making the the sale she had left her job and moved to the West Country to get married. She had thought no more about the Woolworth encounter. A routine shopping trip had taken her into the large modern Woolworth's in Plymouth. To her amazement the back wall of the store had been dedicated to a huge display of her Homemaker design. It had clearly passed its test. As the weeks passed the story played out in the press. Homemaker had become first a best-seller and then a phenomenon. As sales boomed, the design drew favourable headlines, including "Stylish & Elegant. Can it possibly be Woolworth?". Design gurus described the simple pattern, which showed the silhouettes of modern furniture designs in black on a plain white background, as 'iconic'. Seeney admitted to mixed feelings. She was proud to think that extra factories had opened just to satisfy demand, keeping many of her friends gainfully employed for a number of years, but disappointed that Woolworth had chosen pottery rather than china for the range. She received no royalties from the success that she had inspired, having to make do with accolades from the experts and pride in a job well done.

During the Fifties Woolworth's china and glass built a strong reputation. In the decade that followed it began to compromise, putting the achievement at risk. As its top talent focused on developing new offers of Fashion and DIY, new competitors challenged the dominance of its crockery with lines made more cheaply overseas.

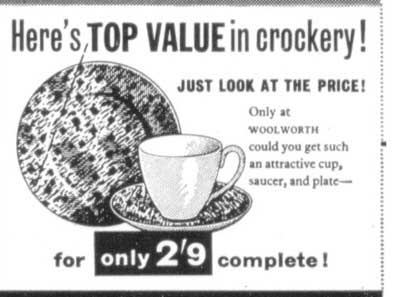

In 1963 the concerns reached Board level. Executives demanded a cheaper budget range. The Buyer responded with very basic cup, saucer and sideplate sets which could be sold for two shillings and ninepence (14p or 16¢). These had echoes of the threepenny lines of pre-war days, but lacked their charm.

The following year the Company embarked on a more comprehensive response to increased competition with a store-wide own-brand. Some items were new, while existing lines were repackaged and began to carry the Winfield name, with the slogan "it's the mark of value".

Strict brand guidelines were imposed on all of the Buyers, instructing them that conservative designs would be more appealing to the mass-market. Over time the own label lines came to dominate the counters. Some were well-made, many were cheap and cheerful and none could deemed stylish. An ultra-low price became the only point of differentiation from competitors.

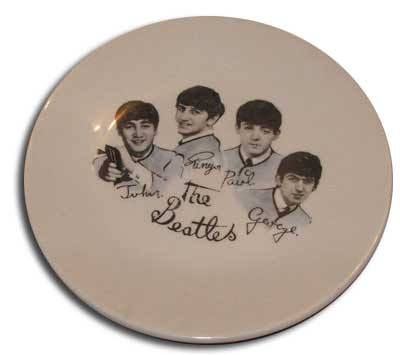

Occasionally there were exceptions to the bland designs. A favourite was specially commissioned Beatles china, which featured signed photos of John, Paul, George and Ringo. These were made by Washington Pottery Ltd of Stoke-on-Trent, and quickly became a hit in Woolworth stores right around the globe. They are now highly collectable.

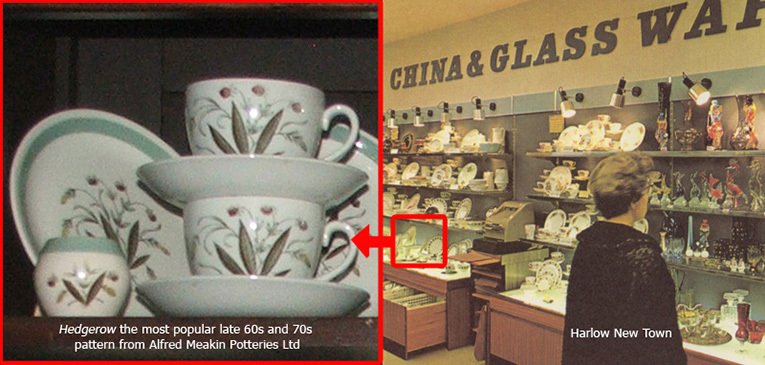

Alfred Meakin Potteries Ltd bucked the trend towards inferior design. It consistently supplied high class patterns and developed a strong following from more discerning customers. It proved that there was still a market for items with a better finish that were designed to withstand knocks and scrapes and retain their distinctive good looks. Their best seller was the Hedgerow design, which built a strong following and was given pride of place on the displays for a number of years. Many British and Irish homes still use a piece or two today, almost fifty years after it first went on sale.

The 1970s also saw the introduction of earthenware and oven-to-tableware products, as well as Noritake fine porcelain china from Japan. The new Shoppers World subsidiary included four pages of china and two pages of glassware in its Argos-like catalogue.

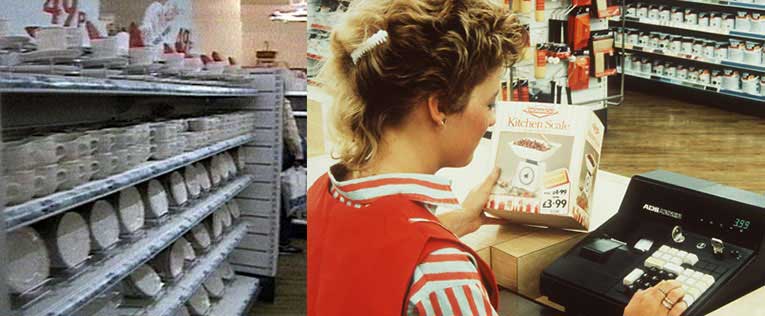

In 1982 Woolworth's American parent company sold its controlling interest in the British subsidiary to a local consortium . The new owners repositioned the brand, specialising in six key product groups . They identified the 'Kitchen Shop' as a key development area. It was given a major overhaul and a new, more stylish range. After successful trials, the new look was rippled through the chain between 1985 and 1989.

At the heart of the new offer was a mix'n'match range of china for 49p and later 69p per piece, kitchen utensils in a choice of either red or buttermilk (a cream colour) and a new own label 'Monarch', which was used extensively on items for the home, kitchen and bathroom. The transformation was driven by Mair Barnes, as Commercial MD. She had joined from the upmarket Department Store chain, House of Fraser. She explained the thinking in a corporate video, saying the new range 'added new style about the home and was modern and up-to-date'. The move re-established the Kitchen Shop as a popular favourite, and a key contributor to the chain's turnaround.

The early 1990s brought a further drive for price competitiveness across the stores, as the parent company Kingfisher embraced the fashionable concept of Everyday Low Pricing ('EDLP'). At Woolworths this was effected as Street Value. The marketing slogan appeared on signs around the stores and in television advertising, but few customers understood it. To support the initiative a few very competitively priced boxed dinner sets were added to the range of china, along with a selection of china mugs for 50p a piece.

In 1997 the Board began work on strategy to make the brand ready for a new millennium. It explored the strengths and weaknesses of each product area, the latest research thinking about future developments, and sought feedback from hundreds of customer panels. The output from this work pinpointed the Kitchen Shop as the area with the most untapped potential. Shoppers acknowledged what had been achieved but wanted more. The Company had built a strong reputation for well-made, durable kitchen ranges, but needed to update the designs and styling to suit modern kitchens and the busy lives of time-pressed families. For example they wanted more designs that were microwave-safe and dishwasher-friendly. Many observed that the products were poorly displayed, contrasting the dull, linear cream shelving at Woolworths with the stylish room-settings on wooden tables in the Department Stores, which lured them to buy, even if the products were inferior.

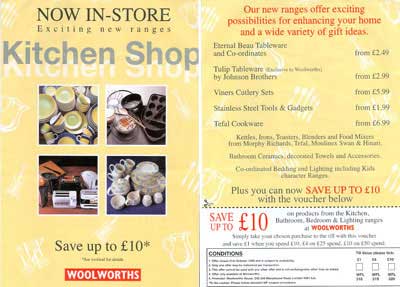

This inspired a resurgence of style, as new look Kitchen shops were added to the stores in city centres and major market towns, and the displays in the smaller stores were extended. The range was given a major overhaul, based on the feedback received. New high-end products were added, including china dinner services and time-saving gadgets for more adventurous cooks.

The new ranges sold well. Customers particularly liked Johnson Brothers' 'Eternal Beau' china, which was carried by every store. Kitchen sales rose rapidly, though the increase did not fully justify the extra space that had been allocated.

To tackle the shortfall, a new ordering service, backed by a 'Woolworths Direct' catalogue, along with smaller Kitchen and Bathroom supplements, was introduced. Shoppers in the smaller stores soon began to use it to get hold of the larger, matching pieces without having to travel to a large town.

The offer went on to see a number of 'about-turns' over the decade that was to follow. Soon after leaving Kingfisher, in 2002 a new CEO, Trevor Bish-Jones, chose to focus on Kids and Celebrations, dramatically reducing the size of the Kitchen Shop. Its remaining space was mainly allocated to expensive luxury lines, while many everyday essentials were dropped,

It is believed that these changes of direction confused customers. While they were all explained away at the time, in retrospect they appear quite bizarre:

- Woolworths Direct was dropped as 'unprofitable' in 2002, but reincarnated it in 2005 as part of a Multi-Channel Retail strategy that expanded the website, introduced a big book catalogue and took orders at the tills

- while the kitchen offer was scaled back in the High Street, it was extended in the out-of-town Big W stores and expanded to fill almost a quarter of the floor space when they became Out-of-Town Woolworths stores

- despite trimming the kitchen displays right back before Christmas, on Boxing Day they expanded to fill a quarter of the whole selling space for a huge clearance sale, 'clearing' products that had never been stocked before. In some branches the event accounted for 80% of annual kitchen sales!

- after pushing up prices substantially between 2002-2007, a new budget range called WorthIt! rocked the industry with prices that were hard to beat, like Porcelain Mugs for 29p, and many electrical appliances for just five pounds.

Sadly just as it appeared that the low-priced WorthIt! approach had turned the tide and attracted new customers into the stores, the chain's bankers pulled the plug. They believed that the business had become vulnerable to a downturn in the market, and refused to provide additional cash to fund the increasing demands of the Group's wholesale division at the height of the credit crunch. The chain collapsed into Administration in November 2008. No buyer was found for the stores as a going concern. They all closed within forty-one days of the collapse.

Today the sideboards and kitchen cupboards of Britain and Ireland bear witness to F.W. Woolworth's century in the High Street. The china and glasses harbour cherished memories of happier times, when affordable style and everyday kitchen essentials were available in every High Street, to pick up, inspect, buy at a till and carry home. Today, unless you live or work in a city centre or have a car, you may just have to click and hope.

Shortcuts to related Home, Kitchen and Garden content

The History of China and Glass at Woolworth

Thrift and economy - DIY at FWW

Blooming good - seeds, bulbs and plants