Repositioning the North American brand

"Mom and Dad don't love us any more"

Back in August 1975, W. Robert Harris, the President of the Woolworth and Woolco division of the Group, had taken the unprecendented step of giving an interview to DM The Discount Merchandiser magazine, and had lifted the hood to show the engine beneath. The Journal had dedicated an entire issue to the revelations about the once-secretive retailer.

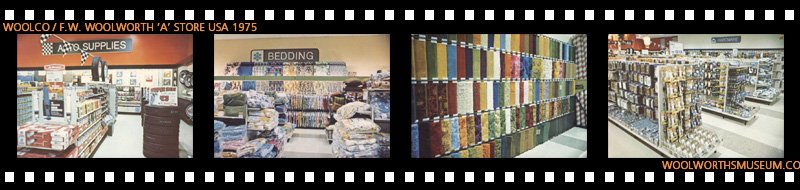

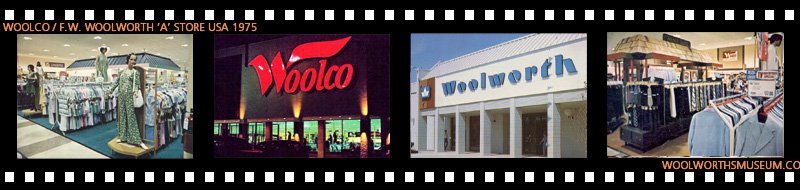

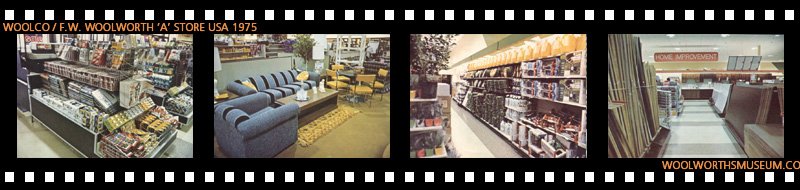

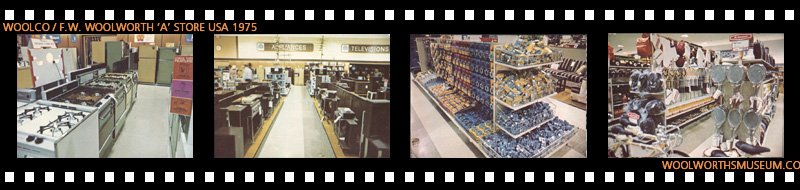

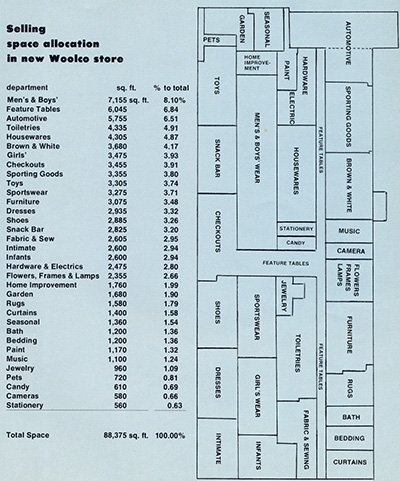

Harris explained that under his leadership Woolco had been integrated into Woolworth. The two chains now had a single set of Buyers and Merchandisers, with both fascias operating in the same administrative Regions and Districts. Pressed about the difference between a Woolworth and a Woolco store, Harris had explained that every store, whatever its fascia, was allocated a range assortment based on its geographical location and local market. He went on to add that the majority of Woolworth stores had resited to shopping centers, or stood directly next door to a mall. He classified such outlets as 'A' stores. Most had 80-90,000 square feet of selling space (7,432 - 8,361 m2), and carried the same extended product range as a Woolco. They could only be differentiated by the fact that space restrictions might curtail the inclusion of Woolco add-on features like car or electrical appliance servicing. This was because the Woolcos were a little larger at around 115,000 square feet (10,684 m2), although he had established that this could be condensed into 90,000 square feet (8,361 m2). So, for Harris, a Woolco and a Woolworth 'A' store were one and the same.

Turning to his 'B' stores, which he preferred to call 'Woolworth Variety', he explained that these were key profit generators, but were too small. Either steps were in train to extend the local selling space to a minimum of 20,000 square feet (1,858 m2), or ultimately they would be closed. Over the previous five years he said that around 550 Woolworth units had been superceded by Woolco and had already gone.

Ominously he admitted that shelf-space productivity at Woolco was too low. Asked "What do you consider a sound sales per square foot goal?" he had replied "We don't believe we can operate profitably on sales per square foot of less than $75 for the total store. We aren't producing that at this point." His recipe to resolve the shortfall was to improve the range of staple merchandise to make shoppers visit more often.

By 1979 it was clear that Harris's medicine wasn't working. As America fell into recesssion clothing sales declined rapidly. Woolco depended heavily on Apparel and Shoes, which accounted for more than 20% of its selling space. As the new decade dawned the giant stores turned from making a small profit to racking up big losses. A new plan was needed to turn the situation around. To achieve this the Board launched a new brand, J. Brannam to sell the designer label clothing brands which had refused to supply Woolco. The name was a play on words describing the store's range which was "just brand names". Existing Woolcos were cut down to release 20-25,000 square feet (1,858 - 2,322 m2) for the marque, which also opened a handful of freestanding outlets. It seems the concept behind the stores may have been inspired by T.J. Maxx (known as T.K. Maxx in Europe), which had been founded in 1976 and continues to sell under the slogan 'designer labels for less' to this day. Early results at J. Brannam were pleasing, but more would be needed to turn Woolco around.

Rather than rely on the tried and tested, but unimaginative, pipeline of people rising through the ranks, Woolworth chose to look outside, bringing in a big name to restore Woolco's fortunes. It headhunted Bruce G. Allbright, the President of Target Corporation, a recent addition to the growing number of chains of out-of-town stores, which had established a winning formula and expanded at a phenomenal rate, rocketing past Woolco in sales and profit to become one of the smash hits of the 1970s retail scene. The new supremo quickly put together a turnaround plan for Woolco, which the Board was happy to buy into. Allbright was given the latitude to do what needed to be done.

Under the Allbright formula Woolco stores were relayed to release space for a J Brannam unit. With the new fascia driving sales growth in fashions, the relay afforded the opportunity to tweak the display layouts to give greater prominence to towards bigger ticket lines like appliances, sight and sound, cameras and sporting goods. In parallel the Buyers would need to source new, more appealing products, negotiating terms with the top marque vendors to complement their broad range of budget lines.

Inevitably range changes in a large retailer take time to put into effect. The process has been likened to turning a super-tanker around, as the captain turns the wheel on the bridge and then waits as the vessel sails on for miles as it slows and switches to the new course. At Woolco many ranges were bought up to eighteen months in advance, as Buyers travelled the world to visit potential suppliers before obtaining letters of credit, bills of lading and managing delivery through the Supply Chain, with containers on the high seas for up to six months as goods made their way to the counter. Allbright would need time to effect his turnaround. There was plenty to do in the meantime. Old lines would need to be cleared to release space. In the short-term cutting and clearing poor sellers tends to be boost the number of items sold, but to reduce the overall takings as thrifty shoppers stock up on bargains rather than full-priced lines.

In Winter 1981 Bud Lynn, the Deputy Chairman of the Woolworth New York parent company, gave an extended interview to a journalist from the British subsidiary's Management Quarterly publication. This gives an insight into the Board's view of the issues at Woolco. Asked about lacklustre trading in the USA he responded:

"With hindsight, it is possible to see that several mistakes were made in the United States when we launched Woolco in 1962, and in consequence that division has held us back.

Originally, Woolco was very heavily oriented toward in-store franchises. About 70 per cent of total sales in Woolco came from licencees. As time went by, the rising costs of rental, labor and everything else needed to operate a retail store rendered it difficult to make money out of sharing profits with a licensee. What we did was, in 1972, to start eliminating franchises. Because you obviously have to give licencees notice, and since they take time running down their stocks, it takes time and momentarily depresses profits even further. One of the biggest franchises has been Apparel Buying Associates, whose contract has just expired. ABA bought children's and ladies' clothing for us, tagged it, and distributed it to our stores for a service fee. Now that fee will become part of our profit. We now have only one licencee, and that is Kinney Shoes, which we own."

He noted other problems too:

"Another problem was that the Woolco stores were too large. They were about 115,000 square feet, and we are now reducing them to 90,000. The part we retain is being completely re-fixtured as well as re-merchandised. The remaining part is being walled off ... In some cases, it's being leased out, in other instances it's being used for a completely new type of Woolworth business.

It's called J. Brannam, which is derived from 'Just Brand Names'. It sells famous brand-name merchandise at a discount price. This type of business has really taken over in the US recently - there are six or seven big operators. ... In the longer term we plan to be very big in this field - with probably 200 outlets by 1984. ... We opened 8 in 1979, another 19 in 1980, and we're aiming for 50 by the end of this year. We opened 10 in one day in Houston, Texas

There was one other mistake when we started Woolco ... and that was our failure to cluster each regional market ... What we should have done was to take one urban area at a time, and stake it out with three or four Woolcos. We are now doing that. We have more than 300 Woolcos in the US at the moment, but we plan to open 25 new ones each year. The profitability of Woolco will be tremendous in years to come, starting in three or four years."

It seems that Lynn and his fellow Board Directors in New York were banking on a miracle, expecting Allbright's arrival to signal an immediate upward surge in sales and profits. Re-fixturising failing stores was a huge sign of confidence in the new man, as was the outline plan for expansion. But they were in for a rude awakening. Sometimes one has to go backwards to go forwards. It was soon clear that the wider Board were unable or unwilling to wait two to three years for the turnaround. There were financial realities to consider. Twenty-year Bonds had been issued to finance the first Woolco openings back in 1962, when the chain had grown rapidly as an act of faith. They were due for redemption, with many more also completing their term in the decade that lay ahead. Raising further money would be hard without a good news story to justify the expenditure.

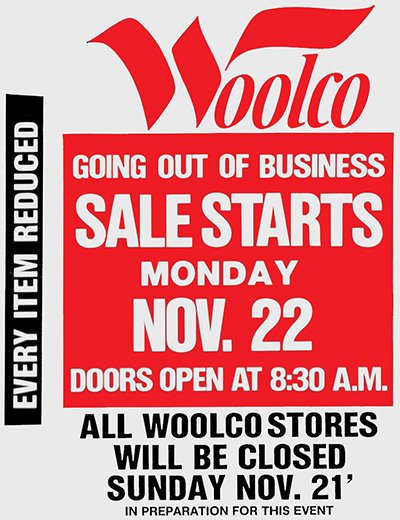

The stark reality was that sales had fallen and profit had nose-dived. The year end of 1981 showed a loss of $19m. By the half-year in 1982, with the revival plan in full swing, it seemed the rate of loss was running out of control, with the store chain $21m down in six months, and projecting a full-year loss topping $50m. Losing patience, Edward Gibbons, the parent Company Chairman and CEO, decided to lance the boil once and for all, recommending outright closure to the Board. It would be painful, it would be expensive but it would liquidate Woolco's inventory of over $1 billion and release funds to spend on more successful areas of the Group. The stores in Canada remained profitable, and would continue trading. The Board agreed.

The closing down sale was advertised nationally in the press and on television. The commercials emphasized that the event came "in time for the holidays" with every item reduced by at least 30%. Press advertisements advised canny shoppers to look out for items that had already been marked down before the bulk discount was applied, which would be at ridiculously low prices.

The unprecedented shutdown was the largest ever seen in the USA. Shoppers flocked to Woolco in the kind of numbers that Robert C. Kirkwood had imagined when he pioneered the concept in Columbus, Oshio back in 1962, but which had never been achieved in ordinary trading. In a cash-strapped economy the high sales at Woolco hit other retailers hard, as well as impacting on the very similar Woolworth 'A' stores which continued to offer many of the same lines at regular prices.

The Company offered generous severance terms to its staff, but still left 25,000 people without a job. The Annual Report later revealed that the overall exit cost was $325m, which was treated as an exceptional item. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the decision to close, City Analysts were impressed by the move. The Corporation's orderly exit, which saw it burying its own dead, was in very marked contrast to the collapse into bankruptcy and Administration that has since become the hallmark of failing retailers.

Brokers were impressed by the Board's "bold decision" to downsize its operations by over 40% and sacrifice $1.8bn of sales volume. But it is an indictment of how Woolco was managed as a business of that scale, that it was not possible to sell all or part of the Company as a going concern, and that rivals were able to rake over the embers, acquiring some of the real estate cheaply from the freeholders in the months and years after closure rather than paying premiums to Woolworth for the locations. Sadly many buildings lay vacant and in decay until they were pulled down.

Gibbons had already shut down another Woolworth chain in 1981. He decided to pull the plug on its operations in Spain, closing and selling the eight stores and the headquarters and warehousing. The move had been driven by union difficulties and a difficult market, he had explained. Before the last Spanish building had been sold, and before the shutters had fallen at Woolco, he entered negotiations with a London consortium to sell New York's 52% share in the British and Irish Woolworth. He portrayed the move as "doing the right thing" for the subsidiary, letting it stand alone after many years of sending more than half of its gross profit back to the USA.

The announcements left Gibbons's number two, Deputy Chairman Bud (John W.) Lynn, with egg on his face. While in London just months earlier, he had justified the Spanish decision, explaining that local market conditions had been difficult. Trade Unions had a veto on even small trading decisions, making it hard to fine-tune the offer. Research had revealed that even the country's largest retailers were sustaining high losses, prompting an orderly exit. In answer to a follow up question about whether New York might pull out of Britain, or sell its golden share, he had responded "I could not. No. We have no desire to sell our interest in the British Company. ... If someone made us an offer for our stake we would be obliged to talk to them in the interests of our shareholders, as we are a public company. However, we have no wish to talk to anyone." Perhaps he chose his words carefully. If the American Parent had not already received the approach, it would get one in the following days. All three of his predictions, spanning the future of Woolco, J.Brannam and Woolworth UK, soon proved to be completely wrong. J. Brannam followed Woolco onto the scrap-heap, after losing more than three-quarters of its sites to the closure, while Woolworth UK faced a management buy-in after the parent company voted to accept a bid every bit as hostile as Brascan's 1979 assault had been in the USA.

Lynn was in for a much larger surprise, when Gibbons died suddenly in October 1982. He had lowered his sights after being passed over for the Group CEO and Woolworth/Woolco supremo roles in 1975. Gibbons and Harris had been brought in from the outside to bring fresh perspective and steely determination. 'Everybody's Bud' seemed happy to cruise towards retirement as an ambassador and troubleshooter, who was consistently sent overseas whenever the Corporation faced a crisis.

Yet the Board chose Lynn rather than a younger rising star to take the helm. He was honoured to lead the Company that he had served for forty years. It seemed Frank Woolworth's promise that a good man could rise from the Stockroom to the Board Room still held true after 103 years.

Lynn's stockroom had been at 5th Avenue and 34th Street, New York in 1942. After serving in the Air Force during World War II he had returned as Store Manager of Madison, New Jersey and had risen to District Manager, before making his name as Head of Sales and Advertising. He was a dyed-in-the-wool variety store man. And now the Corporation's destiny lay in his hands.

Lynn's first challenge was to pick up the pieces. The variety chain had lost over half of its volume with the closure of Woolco, and its central buying and distribution infrastructure needed to be streamlined to avoid Woolworth Variety becoming top-heavy. The stores had been neglected throughout the Woolco years and their identity had become blurred, but nonetheless they had survived. In 1981 Lynn had observed "we are the only variety store with the buying muscle and advertising power of a national chain, so we have a good business. Woolworth Variety continues to gain in sales, and it's becoming more and more profitable every year".

True to his word, the chain was revamped. The big ticket ranges from Woolco were dropped, eliminating household appliances, high-end Ladies outerwear, carpets and building materials. The staple ranges that had been the backbone of Woolworth's for generations were modernised and expanded. This created a family convenience store, majoring on Candy, Stationery and Party, Drugstore, Homewares, Home Entertainment and a comprehensive range of Kids Toys, Fashions and Footwear. As leases expired on the largest buildings they were not renewed, but where a unit showed strong future potential it was fully modernised. Under Lynn's leadership, 35% of stores got a full makeover. New fixtures were arranged in a diagonal herringbone pattern, which in retail-speak made the sides of the gondolas as valuable as the ends, as each store's range assortment was targeted to its local market.

Lynn also capitalized on another strength which the Corporation had developed during the restructuring. It had built the knack of opening small stores quickly, exploiting the trends in many retail sectors. Such small stores could be built from scratch quickly and cheaply, or cherry-picked as acquisitions. They could also be closed or sold equally rapidly. The Kinney Division had already struck upon the highly successful Footlocker athletic shoe format, and had followed it up with Lady Footlocker. Little Folk speciality stores and their bargain Kids Mart outlets were an example of a chain acquired and rapidly developed during Lynn's tenure at the top. Returns from this small store type of retailing were high and showed great potential for the future.

Lynn's enduring achievement was to return F.W. Woolworth Co. to a firm financial footing. During his tenure property disposals helped him to eliminate long-term debt, and to drive an increase in sales, profits and return per share. His long experience helped him to evangelise the changes and to drive through a major programme of cost cutting behind the scenes, that left the Corporation leaner and fitter than it had been for many years.

His love of the heritage had given the Variety Stores one last throw of the dice, but had also sown the seeds of their ultimate demise by developing new brands with higher returns. Bud Lynn had even initiated moves to restore the Woolworth Building to its former glory. Following in the footsteps of Frank Woolworth and US President Woodrow Wilson almost seventy-five years earlier, he marked his upcoming retirement by flicking a switch at Napoleon's desk atop Cas Gilbert's magnificent edifice to illuminate the spire once again for the first time in forty years, restoring it as a beloved feature of Manhattan's evening skyline. Little did he know that in scarcely a decade's time the Woolworth name would be gone for good from the Malls and Main Streets of North America, and even from the nameplate of the Company itself.

Tellingly Lynn's successors, CEO Harold E. Sells and COO Frederick E. Hennig chose to be photographed outside a Footlocker store for their first Annual Report, which was published in April 1987. They planned to build on only part of their predecessor's legacy, accelerating the move into speciality formats and away from the variety stores. Despite US Woolworth sales of $1,972,000,000 and profits of $95m, and Canadian turnover equivalent to US$ 1,472,868,920 and profit of $70.1m, (total sales of $3.44bn and profit of $165.1m) the Report made clear that, in the future, the lion's share of investment would go into the newer brands, which at the time turned over $2.21bn but generated a profit of $240m.

During the new leaders' first year at the helm thirty large Woolworth stores had closed, replaced by 88 tiny specialty mini-me single story units. The chain of full-service variety stores stood at 1,192 stores in the USA and 302 in Canada, of which 120 were huge surviving Woolcos.

By 1989 a further 92 Woolworth Variety stores had closed in the USA, and just one had opened, with 23 more going in Canada, where four had been added. Despite this sales had broken the $4bn mark, up 16.2% in three years, while profits stood at $229m, up 38.9%. The Woolworth-inspired Specialty stores like Herald Square had joined the Specialty Division. That new favorite child had turned over $3.77bn, an increase of 70.6%, and had generated $350m of profit, up 45.3%.

Woolworth Variety might have lost in the competition for investment with its parent's new children, but it was not dead yet.

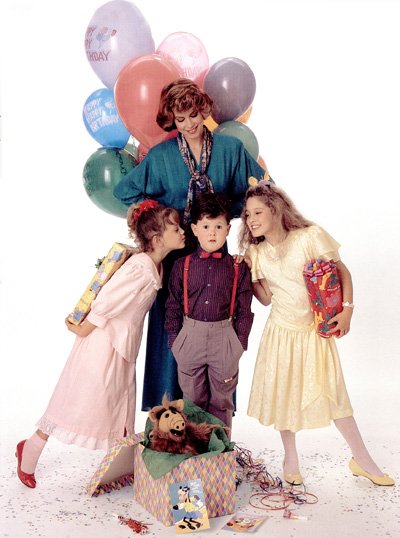

In many mature companies a year-on-year increase in profit of 10%, sustained over three years against a backdrop of divestment would be seen as a stellar performance. But for the parent company, Variety remained very much in the dog house. The back cover of the 1986 Annual Report, which is shown below, tells the sad, sad story of the unloved old 5 &10¢ clearly, without words. Mummy and Daddy have got new babies and don't love us any more.

Shortcuts to related content

Acquisition of B&Q by F.W. Woolworth & Co. Ltd.

'21st Century Shopping', Concept Store

The Cornerstone Business Strategy

Launch of The Video Collection

Launch of exclusive Ladybird licence

The Lighter Side of the Eighties at Woolworths

Site Navigation